Social Carbon Pricing – Energy Costs Tend to Zero?

We assess that Social Carbon Pricing could be a contributor to pushing the marginal cost of electrical energy production to tend to zero over time. This outcome would create a social and economic wealth generating paradigm shift as well as contribute to preserving or improving our global environment.

President Joe Biden’s advisors have been reassessing the social cost of carbon (SCC) since his inauguration 2021, in order to determine an accurate value. An accurate value/cost of the SCC is needed to correctly determine the social benefits of reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

The cost per ton of carbon is the price assigned to the emission of one metric ton of carbon dioxide (CO2) or its GHG equivalent such as methane (CH4) or nitrous oxide (N2O). The cost can vary based on a specific policy, market or program.

In February 2021, the Biden administration announced an initial estimate of $51/metric ton of CO2 equivalent (tCO2e). Debate is ongoing among scientists and economists, with the analysis involving decisions about what climate costs to include and whether or not government policies should pay now or later.

The social cost of carbon (SCC) aims to address the social and economic impacts of reducing GHG emissions for vulnerable and marginalised populations. By putting a price on carbon emissions, revenues generated can be used to invest in social programs that support communities and individuals most affected by the transition to a low-carbon economy.

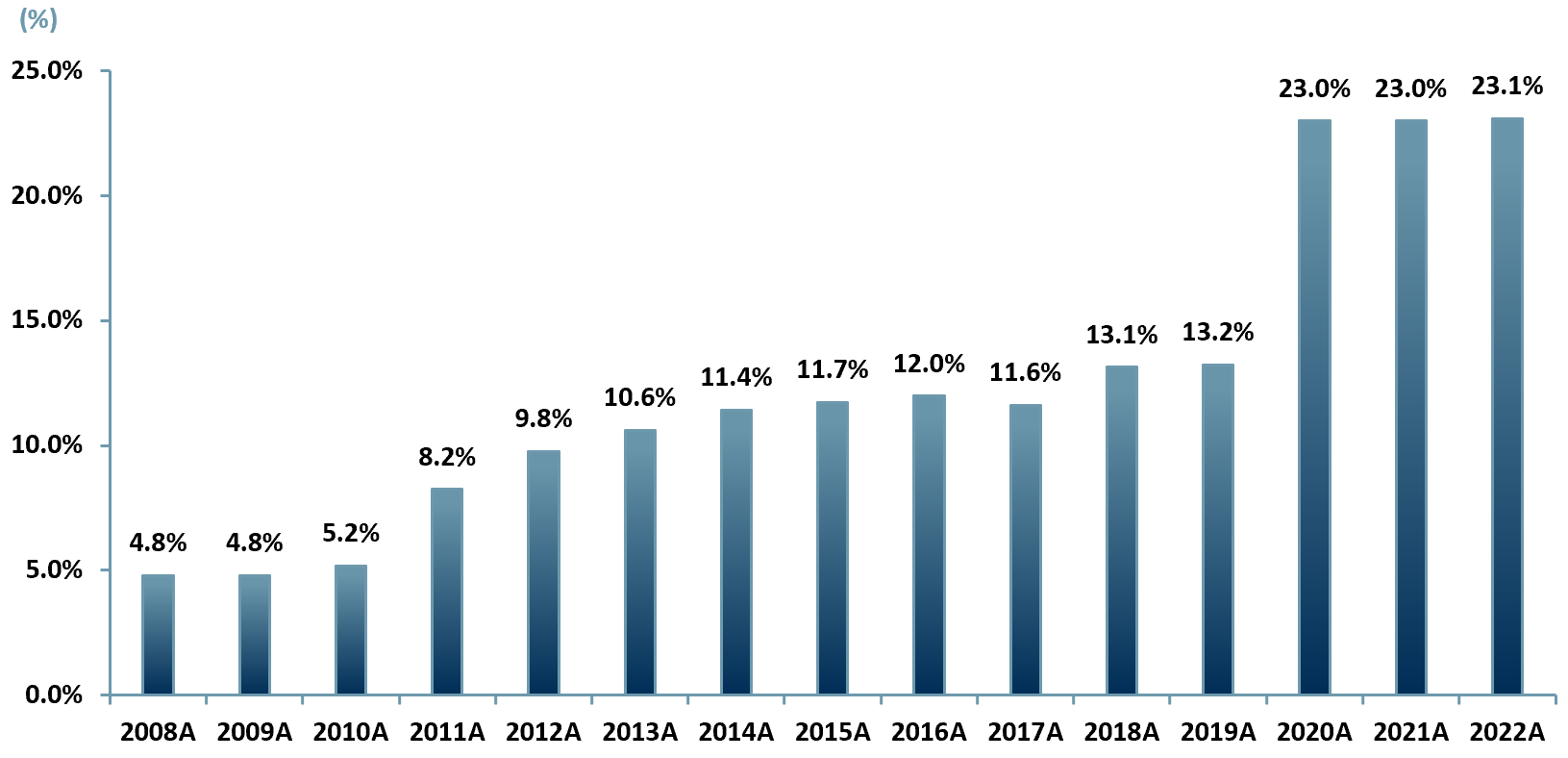

The transition to a low-carbon economy is both environmentally effective and socially equitable. As a result of the Covid pandemic, sustainability came under the spotlight. The share of GHG emissions globally covered by carbon pricing instruments increased by 204% from 2019A to 2020A (exhibit 1).

The share of GHG emissions post-Covid increased due to several factors: 1) government action increased as governments saw the recovery from Covid as an opportunity to transition to a low-carbon economy, 2) Covid increased awareness and public support for carbon pricing policies, 3) countries recognised that investing in low-carbon technologies and carbon pricing policies would stimulate economic growth, and 4) the Paris Agreement has provided a global consensus and partnership to fighting climate change.

Exhibit 1 – Global share of GHG emissions covered by carbon pricing 2008-2022A

Sources: ACF Equity Research; World Bank.

Sources: ACF Equity Research; World Bank.

What is Social Carbon Pricing?

The social cost of carbon (SCC) or carbon pricing is not a new phenomenon. The concept of putting a price on carbon emissions was developed in the early 1990s by economists using market-based mechanisms (i.e. emissions trading or a carbon tax) to address/mitigate climate change.

The term social cost of carbon (SCC) was first used in a 1992 US National Academy of Sciences report. The report recommended that policymakers consider the potential social and environmental costs of carbon emissions in their decision making.

SCC is seen as critical in mitigating climate change and achieving the Paris Agreement goals. Since 1992, the SCC concept has been refined and expanded. SCC has become an important and invaluable tool for policymakers’ decisions to assess the economic impacts of climate change and inform decisions about mitigation policies.

In 2008 the US government began formally incorporating the SCC into its regulatory analysis. By 2010, the Interagency Working Group (IWG) on the Social Cost of Greenhouse Gases was established to coordinate the development of SCC estimates across different federal agencies.

SCC estimates have been used, and continue to be used, in regulatory and policy contexts such as setting fuel efficiency standards for vehicles, to evaluating impacts of energy efficiency programs, to assessing the costs and benefits of climate mitigation policies.

Social carbon pricing is increasingly adopted by global governments and businesses as a way to address the challenges of climate change and economic inequality.

Carbon Pricing vs. Carbon Tax vs. Carbon Credits vs. Carbon Allowance

In our assessment, a progressive hypothecated carbon tax based on a polluter pays principle integrated into a trading system is the solution most likely to achieve sustainable outcomes. It has the advantage that it can trigger change at speed and generate value at the same time by nudging and corralling emitters and markets.

Carbon pricing, a carbon tax, a carbon credit and a carbon allowance are all different mechanisms for putting a price on carbon emissions, but they differ in their design and implementation.

- Carbon pricing, is a market-based approach that puts a price on carbon emissions. It can be implemented through either a carbon tax or a cap-and-trade system.In a carbon tax system, a price is set on each unit of carbon dioxide or equivalent emissions and whomever is producing emissions (government or business) must pay a tax on the emissions they produce.In a cap-and-trade system, a cap is set on the total amount of emissions that can be produced and companies are issued allowances for their emissions. Companies can buy and sell these allowances, creating a market for carbon emissions.

- A carbon tax is a form of carbon pricing where a price is put on each unit of carbon dioxide or equivalent emissions. The tax is a financial incentive to encourage emitters to reduce their GHG emissions, because they are obligated to pay for any damage caused by emissions.The tax amount is based on several factors such as the SCC. A carbon tax can be a flat rate per unit of CO2 or it can increase over time to provide an additional incentive to reduce emissions.The revenue generated from a hypothecated carbon tax can be used to fund government programs or to offset the costs of climate change mitigation measures (e.g. investments in renewable energy).

- A carbon credit, also known as a carbon offset, is a way for companies or individuals to offset their emissions by purchasing credits that represent reductions in emissions somewhere else. E.g., a company invests in a project that reduces emissions in a developing country (offsetting project) and then receives credits for the emissions that are avoided. The company can then use these credits to offset their own emissions in their country of operation.The carbon credit is sometimes considered a ‘Band-Aid’ solution because it does not directly address the reduction of emissions. It is not favoured as a long-term solution because the effectiveness of carbon credits relies on the integrity of the offsetting projects. There are ongoing concerns as to the quality of offsetting projects.However, carbon credits can be seen as favourable for the renewable energy transition period, if they improve energy efficiency and the electrification of transportation. The credits can provide emitters with a way to offset emissions that are difficult or expensive to eliminate in the short-term, while still supporting carbon reducing projects in other sectors or regions.

There is an alternative to carbon credits.

- A carbon allowance is a permit that allows the holder to emit a certain amount of GHG emissions. The allowance amount is dictated by governments as part of a cap-and-trade system – a cap is placed on the total amount of emissions that can be released over a period of time.The European Union Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) works on a 5-year trading period. The US Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) works on a 3-year period.A shorter period of time creates urgency among regulators to reduce emissions more quickly. A longer period allows for a gradual reduction in emissions, i.e. more capital and time flexibility.

The Carbon Pricing Market

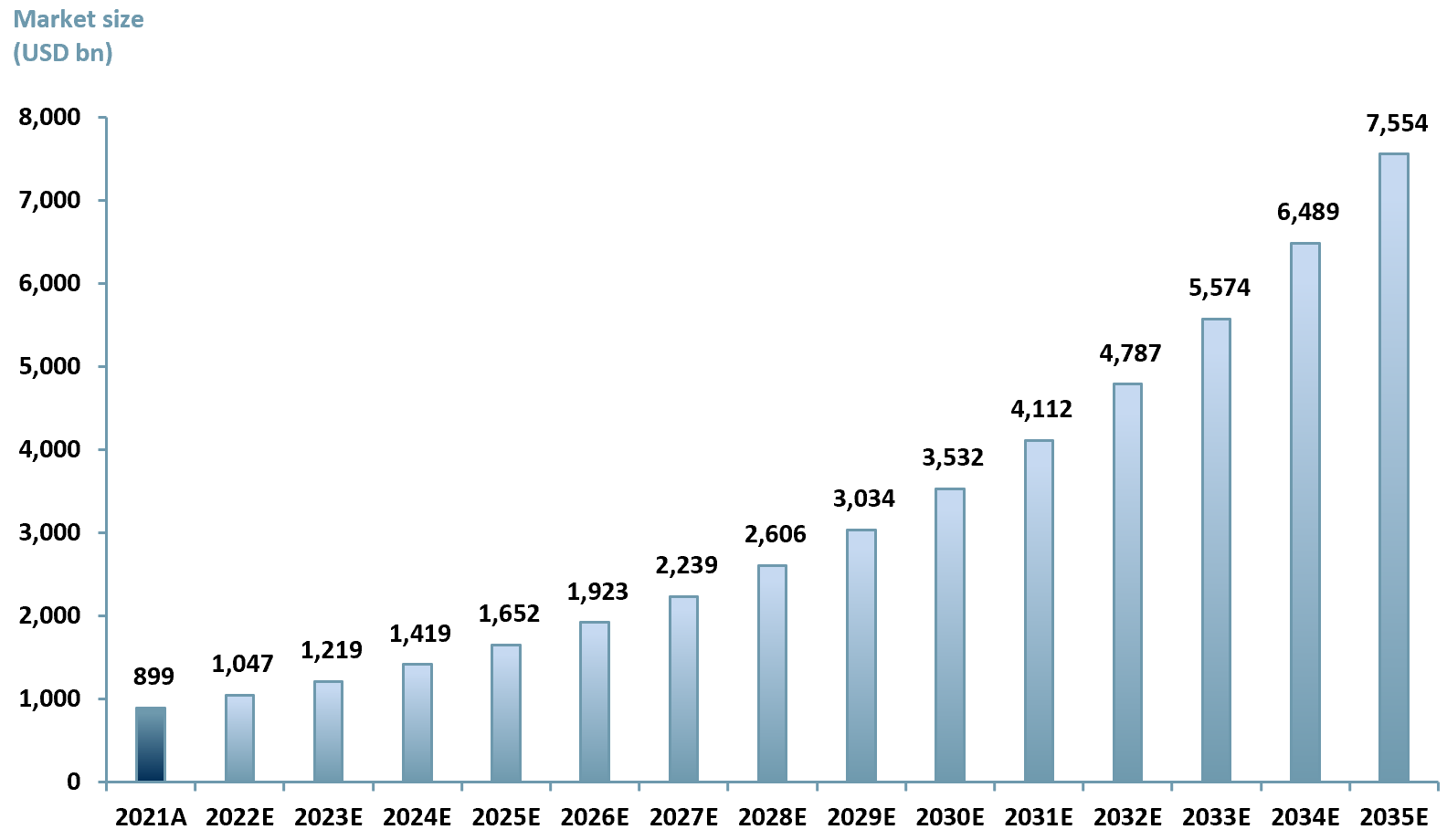

The carbon pricing market is valued at $899bn in 2021A, up ~165% versus 2020A (Refinitiv). This is the value of carbon taxing and carbon credits, or carbon allowances, bought and sold on a cap-and-trade system.

In Exhibit 2, we forecast that the carbon pricing market will surpass $4,000bn by 2030E up from $899m in 2020A, based on a CAGR of 15.25%.

The price increase is on the back of governments and corporates facing increasing pressure to deliver on the Paris Agreement climate targets – i.e. the reduction of GHG emissions by at least 50% by 2030.

Exhibit 2 – Carbon pricing market 2020A-2030E

Sources: ACF Equity Research; Refinitiv.

Sources: ACF Equity Research; Refinitiv.

Countries and regions that have carbon pricing initiatives or proposals include Canada, Japan, Australia, New Zealand, Switzerland and the UK. The major global carbon pricing markets are:

- European Union Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) – The EU ETS was launched in January 2005. It is the largest carbon pricing market in the world and covers 10,000+ installations (facilities/plants that generate electricity) in 31 countries in the EU, Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway.

- Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) – The RGGI was launched in September 2008. It covers the north eastern states of the US (ME, VT, NH, MA, CT, RI, NY, NJ, DE, MD, VA) and takes a regional approach.

- California Cap-and-Trade Program – The California Program was launched in October 2011. It covers the electricity, industry, transportation and natural gas sectors.

- South Korea Emissions Trading System (KETS) – The KETS was launched in January 2015. It covers the power, steel and petrochemical sectors covering 600+ companies.

- China Emissions Trading Scheme (CETS) – The CETS was launched in February 2021 and covers the power, steel and cement sectors. It covers 2,100+ companies, which are responsible for ~40% of China’s GHG emissions.

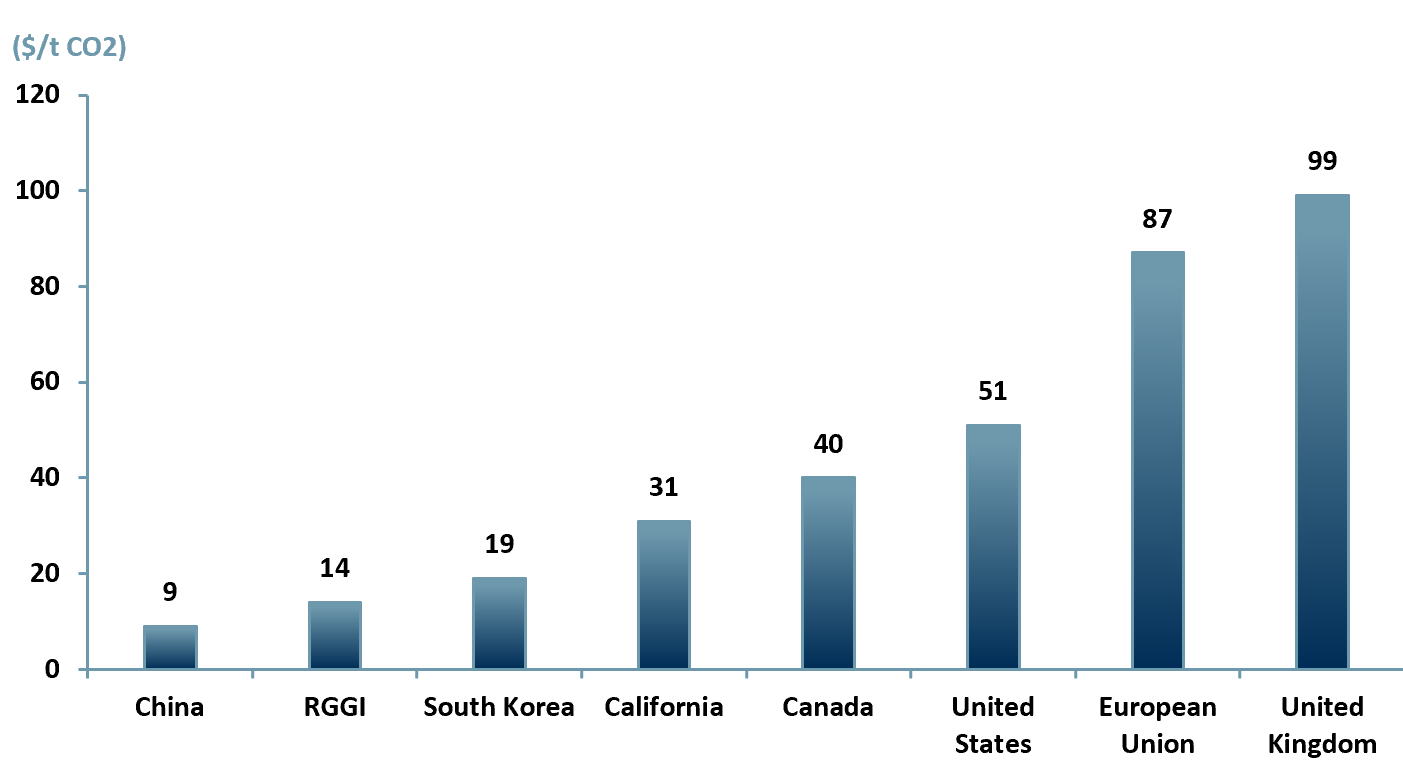

In exhibit 3, we showcase the price of carbon traded globally as of April 2022 in select regions based on those covered by an Emission Trading System (ETS) referenced above.

Exhibit 3 – Carbon trading prices covered by Emission Trading Systems (ETS) by region April 2022

Sources: ACF Equity Research; World Bank.

Sources: ACF Equity Research; World Bank.

Carbon Pricing Pros and Cons

We accept that carbon pricing is a controversial and complex policy issue because it involves balancing economic, environmental and social considerations. On the one hand carbon pricing is viewed as being able to reduce GHG emissions and on the other hand it is viewed as creating an unnecessary burden on lower income communities, that the hyper industrialised economies, in particular, were never forced to face during their high growth and wealth generation periods.

Carbon Pricing Pros:

- Encourages innovation and new technologies by incentivizing businesses and individuals to find new and more efficient ways to reduce emissions. This in turn grows GDP.

- Generates revenues for governments that can be used for funding climate mitigation and adaptation programs, research and development of clean energy technologies, or rebates for low-income households.

- Levels the playing field for businesses, making it easier for clean technologies and renewable energy sources to compete with fossil fuels.

- Encourages behavioural change in individuals to adopt low-carbon behaviours, such as using public transportation or reducing energy consumption.

Carbon Pricing Cons:

- Creates potentially negative economic impacts by increasing the cost of goods and services (though we note this is not always bad economics), particularly those that are energy-intensive, which comes with the risk of disproportionately affecting low-income households.

- Creates a regulatory burden and compliance costs for businesses, particularly small and medium-sized enterprises.

- Creates a market distortion by putting businesses in countries with carbon pricing at a competitive disadvantage compared to those in countries without it by increasing the cost of production and reducing profitability.

- Creates potential for an evasion market (which also destabilises social structures by eroding trust systems) because carbon pricing can be difficult to enforce and there is a risk of carbon leakage (i.e., companies relocating to countries without carbon pricing to avoid paying the carbon price).

The pros and cons of carbon pricing must be carefully weighed and balanced to ensure it is an effective, efficient and equitable (in order to get global buy-in). It is important to design carbon pricing policies that take into account specific economic and social contexts of different regions and countries.

Carbon pricing is also a crucial mechanism that we assess will, in the end, lead to cheaper global energy than fossil fuels can provide, we can see a longer term outcome much like telecommunications were electrical energy marginal costs tend to zero – the dream of fusion pricing without the fusion reactor.

Authors: Renas Sidahmed and Christopher Nicholson. Renas is ACF’s Head of ESG and a Staff Analyst, Christopher is Head of Research see their profiles here.

![Climate change and the [re]emergence of millet Climate change and the [re]emergence of millet](https://acfequityresearch.com/wp-content/webpc-passthru.php?src=https://acfequityresearch.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/ACF_Millet-a-new-sustainable-market-_Twitter-470x320.jpg&nocache=1)