Barbarians are back at the gate

The hostile takeover cycle remains unabated in 2022 – driven by sustainability/ESG and a desire by investors to shift from a passive to an active investment strategy during a prolonged period of market volatility.

A new wave of activist investors is pushing the ESG agenda. Whilst these investors target large-caps primarily, smaller companies remain extremely vulnerable. As the hostile M&A trends continue, companies are re-adopting poison pill strategies. But poison pill strategies are quick fixes with long term negative consequences for companies and investors alike.

A poison pill is a defence tactic that company managers and non-activist shareholders use to prevent or discourage takeover attempts that undervalue the longer-term potential of a company. This defence tactic allows shareholders to purchase additional company shares at a discount to dilute the ownership interest of a new hostile party.

These poison pill defence tactics are short term. To effectively defend themselves companies should consistently assess their vulnerabilities.

Persuading investors that a long-term payout is more valuable than a short-term one is not necessarily a straightforward challenge for company management teams. Telling the investment story and presenting future prospects is always best done when it is led by third parties that specialise in this activity.

Smaller companies in particular, require the support of long-term stable investors to maintain a constant flow of capital. The nature of smaller companies is a constant struggle between liquidity and volatility, i.e. establishing a stable, growing share price and fungible stock without volatility, and in this way avoiding or repulsing the attentions of entities or groups of entities engaged in hostile takeover strategies.

Driving the hostile takeover trend in 2022

Hostile takeovers are expected to continue in 2022 due to the following:

- As the pandemic continues, boards are hesitant to make major decisions, such as disposals of non-core business units;

- Bidders resort to hostile tactics as they are eager to execute a purchase while share prices undervalue the assets, i.e. buying cheap. Which means depriving longer term shareholders of the value that compensates for the initial risk they have taken;

- Some industries and companies continue to trade below pre-pandemic levels, resulting in perceived high deal premiums that make defences

- difficult and encourage short term investors, in turn increasing price volatility. (We except Healthcare where deal premiums are high relative to 5 years ago);

- The rise in SPACs – private enterprises going public. SPACS are a quick mechanism to public company status, where companies going public forgo many of the disciplines associated with the transition from private to public status – this leads to inexperienced, vulnerable and under prepared and under supported management teams unable to extract maximum value for shareholders.

Why smaller companies should be on their guard

Smaller companies are at risk of hostile takeovers because their share prices are often very far from reflecting fair value.

Smaller companies often struggle to attract long term supportive shareholders because share liquidity is low and so share prices are volatile. High share price volatility is unattractive to longer term shareholders but highly attractive to day traders, investors with shorting strategies and hostile takeover strategies.

Low liquidity and high price volatility is unattractive to longer term investors because establishing an asset value is particularly difficult and because of the reduction in fungibility of the shares. Low share fungibility increases risk and so contributes to lower valuations.

These liquidity and volatility conditions create a downwards self-reinforcing valuation spiral, which means that hostile takeovers tend to look attractive on a relative basis but very often do not reflect anything close to the longer-term fair value of the targets.

As a result of the above factors, smaller company share prices are also easily manipulated or disproportionately influenced by seeded gossip and short termism. While improving corporate governance practices and shareholder engagement is a worthy defence mechanism, telling the investment story well is the real key to long term defence and achieving fair value from a bid.

Small O&G companies are particularly vulnerable because of the green energy transition. Many O&G are incorporating this transition into their O&G operations in an effort to be perceived as energy companies with a sustainable future, making them of interest to potential bidders. Brown assets are on their way out and green assets in.

While hostile takeovers might be a highly attractive option for activists, they are far from entirely successful and they do not generally benefit other non-activist shareholder classes.

The RJR Nabisco story becomes pertinent again

In Bryan Burrough’s and John Helyar’s 1989 Barbarians at the Gate: The Fall of RJR Nabisco is cleverly articulated to show how hostile operations do not provide the expected returns.

The ‘celebrated’ leveraged buyout (LBO) of RJR Nabisco did crystallise fair value for shareholders – RJR was not sold to the highest bidder. At the time of the deal in 1989, RJR Nabisco went to Kohlberg Kravis Roberts (KKR) for $109/share. By 1991 when the company went public, it was valued at half the price.

Via the LBO process RJR Nabisco was saddled with debt. RJR Nabisco was forced to divest several of its divisions following the acquisition because of the LBO debt burden. This resulted in 2,000+ workers losing their jobs.

Tobacco litigation over prices further set RJR Nabisco back. The debt-ridden company was forced to reduce marketing spend and was unable to compete with key competitors Philip Morris and Marlboro. RJR Nabisco was forced to sell its international business operations to Japan Tobacco for $8bn to salvage remaining value.

All of the above negative consequences were direct effects of a hostile takeover. No one held RJRs management team in esteem for the LBO or the subsequent outcomes.

In the RJR Nabisco story, higher premiums led to higher levels of debt and a dissolution of operations.

While the majority of hostile takeovers happen up the hill (with large-caps), the data suggests they are coming down the hill with some force.

UK M&A market

US businesses and private equity funds are taking an interest in UK public companies on the London Stock Exchange (LSE) main market and the Alternative Investment Market (AIM) – two of the homes of UK smaller and mid-cap companies.

According to Pinsent Masons (UK international law firm) the interest from the US comes from the resilience of UK companies in the face of the pandemic combined with their depressed share prices (undervaluation) – making them attractive targets to those pursuing hostile takeover strategies.

UK firms are relatively ‘cheap’ compared to US companies based on a price-to-earnings (P/E) ratios. The FTSE 250 (mid-caps) traded at 9.9x and the FTSE 100 (large-caps) traded at 15.6x versus the S&P 500’s 26.9x (Refinitiv).

Though PEx is not typically cross boarder useful because it depends on relative tax regimes, the corporate tax rate in the US and the UK is broadly comparable. With US large cap PEx ratios at nearly double those of the UK equivalents in the period, it remains suggestive of a significant opportunity for hostile takeover strategies.

The UK’s Takeover Panel (Panel on Takeovers and Mergers) regulates takeover bids and M&A transactions in accordance with the UK Takeover Code. The main purpose of the code is to ensure shareholders of the acquiree and acquiror have an opportunity to decide on the value of a takeover.

The Potam regulation works mechanically but it is not necessarily ensuring fair value is achieved and it is difficult to see how to legislate for fair value M&A. The real answer is in consistent and persistent story telling.

In 2021 there were 53 prospective deals subject to the UK Takeover Code involving companies on the LSE and AIM. Of the 53 there were 23 solely US bidders or 61% of the total, 16 solely UK bidders and the remaining 14 a combination of UK & US & other overseas.

The total value of all the above 53 prospective deals subject to the UK Takeover Code was £65.2bn (Lexis Nexus), an average deal value of £1.23bn suggesting a very much smaller cap takeover wave.

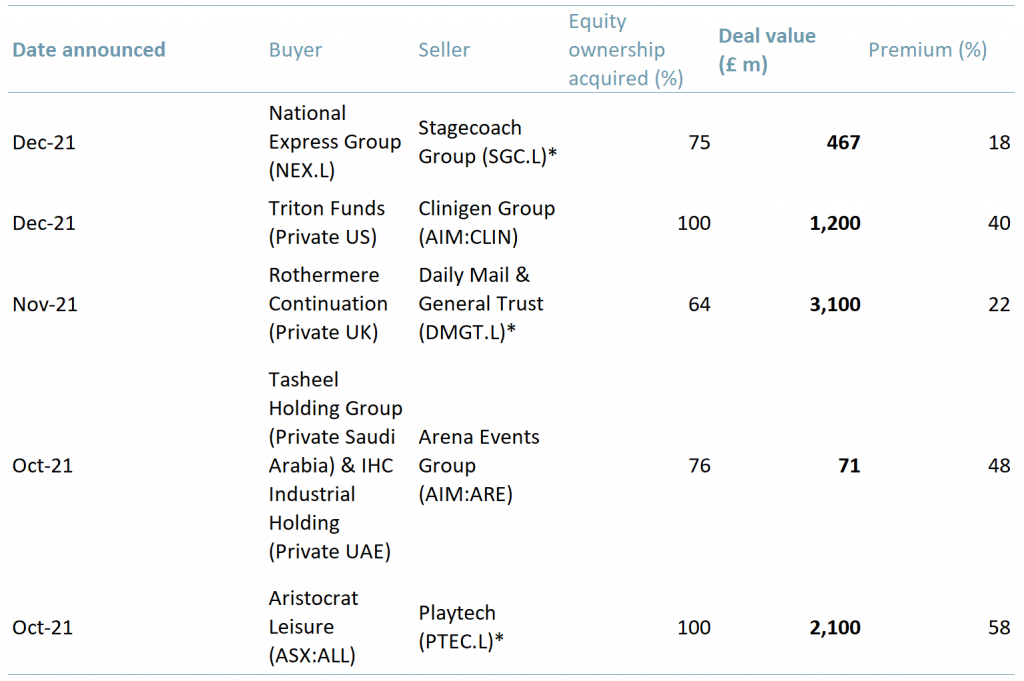

In exhibit 1 below, we showcase five M&A deals in 2021, which include AIM listed companies. Given AIM listings have relatively low MCAPs and share prices, we expect growth of hostile takeovers on AIM (and the standard list) in 2022.

Exhibit 1 – UK M&A deals 2021A

Sources: ACF Equity Research Graphics; Ashurst. Notes: SGC.L opted out in 2022. DGMT delisted in Dec 2021. PTEC rejects deal in 2022.

Sources: ACF Equity Research Graphics; Ashurst. Notes: SGC.L opted out in 2022. DGMT delisted in Dec 2021. PTEC rejects deal in 2022.