Greenland mining – little known and mostly untapped critical minerals

Current investor interest is limited but it should not be. For some time now only the most dedicated and or most specialist investors in mining (excluding Jeff Bezos’, Michael Blomberg’s and Bill Gates’s interest in Bluejay mining’s progress) have persisted with Greenland. There is a lot to be positive about – below we set out and acknowledge some of the perceptions and help identify what is changing.

In our view, the reasons most mining investors and investors in general are wary of Greenland is the perception of a harsh environment and anticipated high costs to explore, develop, process and to get to market compared with other jurisdictions. They are also wary of limited infrastructure, unpredictable policy changes, a disappointing number of operational mining successes and no large-cap miners to acquire explorer and developer assets, i.e. no exit routes. Chinese control of critical mineral commodity prices has not aided the situation.

However, we assess much is misunderstood and much is changing about the Greenland minerals opportunity. Nevertheless, the top quartile minerals are probably still the real investor prize, i.e. economically rare concentrations and or critical applications e.g. Amitsoq Graphite (GreenRoc, GROC.L), Green Mountain and White Mountain anorthosites (Hudson Resources HUD.V and Lumina Sustainable Materials (private)). In our peer group table below we list other interesting opportunities.

Investors can’t see large cap miners on the ground in Greenland and so fear there are no exits for juniors – this is a misunderstanding

Large-cap miners are maintaining a clear interest in Greenland. For example, Anglo American (£23bn MCAP, AAL.L) and Rio Tinto (£88bn MCAP, RIO.L) have previously explored in Greenland – present on the ground and, we assess, in reasonably constant conversation with juniors. There is also evidence of growing large-cap interest again in Greenland’s resources.

Kobold Metals (private), backed by billionaires Bill Gates and Jeff Bezos, signed a JV with Bluejay Mining (JAY.L) in 2021 in return for a 51% stake in the Disko-Nuussuaq project in west Greenland. Kobold/BlueJay is exploring to uncover a ‘mirror deposit’ at the scale of the Norilsk-style Ni-Cu-Co-PGE bearing magmatic massive sulphide (MMS) accumulations in Siberia, which are found on the opposite side of the Arctic Ocean. These players are looking for world-class resource opportunities, which Greenland offers.

As of mid-2023 Greenland had just two mines in the production phase – the progress rate has made investors wary

- The Aappulatuttoq ruby and sapphire (corundum) mine is owned by Greenland Ruby (private) situated 160km south of Nuuk in Southern Greenland and logistically supplied by a local small port and a helistop. The resources were defined in 2002 and mine construction began in 2014. The mine closed in 4Q23A due to rising debt and poor sales. Greenland Ruby is currently trying to sell its remaining inventory.

- The White Mountain Anorthosite Mine is the only operating mine in Greenland as of 2024 (several other mineral projects have received exploitation licenses but have not yet gone into production). The White Mountain anorthosite mine is located in Central West Greenland and has a 100-year expected life and aluminium oxide content of 32%.

Anorthosite is something of a potential ‘future material’ as well as having a current wide range of industrial uses from construction surface finishings to fibre glass production, green alumina and CO2-free cement.

There are, coincidently, a lot of anorthosites on the moon. These anorthosites are concentrated at the Lunar Highlands (brighter parts of the moon). The Lunar highlands are areas where NASA and others plan to set up bases.

White Mountain is now controlled by Lumina Sustainable Materials (private) and, we understand, is now revenue generating. White mountain was originally controlled, developed and constructed by Hudson Resources (TSXV:HUD.V OTC:HUDRF). HUD.V’s position has since decreased to a 31% minority (passive) interest. It should be noted that Hudson built the mine relatively inexpensively, at around C$ 45m.

Most investors think all of Greenland is arctic and so doing anything is comparatively expensive compared to other high quality mining jurisdictions, but this is a blanket assumption and broadly wrong. Much of Greenland’s current mining opportunities have good access to tidewater, which is present along much of Greenland’s coastline.

According to Hudson Resources, it shipped its first White Mountain anorthosite load of 14k tonnes to North America to its offtake partner in 2019. Unfortunately, the shipment became contaminated during unloading and was unsaleable, leading to a 4-year insurance claim process. Though this event was extremely painful for investors and company management, it is, in fairness, pain caused by a North American issue and not a Greenland issue.

Combined with Covid, the timing could not have been more unfortunate for HUD.V investors. The experience has caused HUD.V to pivot its business and focus on its 100% owned Gronne Bjerg (Green Mountain) Greenland anorthosite project, where it will re-deploy its cash resources, which as a result, remain relatively healthy at ~C$3.5m. Based on our recent research discussions with Hudson’s management, the Greenland minerals opportunity appears to remain central to Hudson Resource’s plans, though HUD.V now looks more like a vertically integrated tech/materials R&D play.

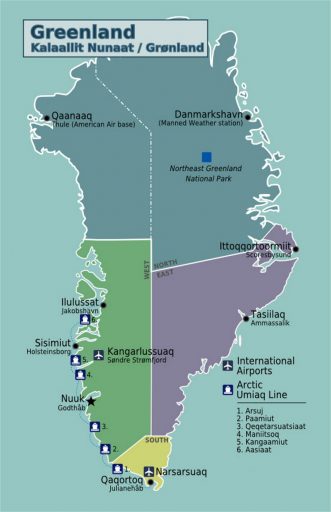

Exhibit 1 – Greenland – an introduction

Sources: Government of Greenland.

What is different now about Greenland to suggest that investor perceptions and so interest could change?

- Investors have been concerned about Greenland logistics (and infrastructure) – Greenland’s environment is getting less harsh. Unfortunately and indeed somewhat ironically, global warming for which Greenland’s minerals are part of the solution is effecting this environmental change – ice receded further than ever before in 2023.

- Investors have thought that getting to market and regular cash flows are a challenge for Greenland miners – Seaways are now open for more of the year, making getting to market for more months of the year much more probable, which equates to more predictable and higher visibility potential cash flows.

The reality is that Greenland has deep fjords for big ships. Coastal mines close to tidal flow do not have particular challenges getting minerals out and suppliers in. Shipping costs per tonne once on the Ocean are the same for getting minerals either to North America or to Europe because of Greenland’s strategic location in the mid-North Atlantic Ocean.

- Investor misperception of an extraordinarily challenging mining environment – At least in the southern tip of Greenland, the climate is much more akin to Northern Scotland than the Arctic (and always has been).

- Investor perception that Europe will never move enough to secure alternative supply lines – Russia’s weaponisation of critical resources in relation to the Ukraine war has created a sharp stabbing pain for Europe and jolted it into an alternative supply focus. Europe moved in a short time frame to alleviate the worst symptoms of Russia’s actions with respect to energy supplies.

Russia is clearly intent on increasing European (and US) commodities pain where it can – for example, the transformation of the Wagner group to an official arm of the Russian military machine intent on and equipped to support Russia’s anti-western political and economic agenda in Africa and elsewhere.

- ‘Key commodities prices are controlled by China, which has an unscrupulous view of market price manipulation’ – China’s dominance of critical materials supply chains is now at the forefront of both US and European strategic thinking. Greenland is a natural part of a strategic supply chain for Western-style economies, politically, militarily, economically and geographically.

Critical mineral prices, for example for graphite and REEs, are controlled by China and are currently ‘artificially low’ to discourage non-Chinese exploration and development – The need for Western supply chain independence, will we suspect, force Western economies into making mining investment more attractive (lower risk for investors), for example by speeding up permitting. This does not mean more lax legislation, it means clearer, simpler and faster administration.

Whatever China does now to control critical mineral pricing does not have an indefinite lifespan, demand will do the rest and China’s policies will only serve to accelerate Western government support for the search for alternative resource and processing solutions outside China. AI will play its hand in both processes.

If investors think the West will want to avoid being held to ransom by China and Russia, then the next three years of legislation and incentivisation will be pivotal.

- Greenland’s mining policy environment and approach have had ‘switcheroo’ characteristics and investors have found this uncertainty unappealing – Whilst true in the past, recent mining policy news from Greenland suggests much greater stability is already here. Perhaps Greenland has finally found its way to a policy raft or approach that all political parties can agree upon, thereby providing policy stability, which is critical to the investor mindset.

GreenRoc (GROC.L, Graphite) management recently indicated to us that the Greenland government is now taking material and solid steps to encourage and support junior miners by, for example, easing the process required to obtain a mining licence.

- It takes 10-14 years to develop a critical mineral mine often because of geological complexity – REE demand is expected to triple by 2040, we think it could be faster because of a range of innovations that include better data collection techniques, lower cost, faster data analysis and improved real-time cost-effective communications infrastructure between HQ and site (LEO satellite constellations).

- Where are the big players such as BHP to buy out the smaller developers to deliver returns to smaller explorers and their investors? – The mega-cap acquirers are present, they are looking and they keep in contact with the smaller explorers.

What investors should know about Greenland as a starting point

- MiMa was established by the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland (GEUS) in 2013 to assess Denmark’s lack of mineral resources and how that impacts its economy. (Greenland is an autonomous territory within of the Kingdom of Denmark.)

- The critical 38 – According to the MiMa report in 2023 there are ~38 critical raw materials found in Greenland including the rare earth elements (REEs), niobium, platinum group metals, tantalum, titanium and graphite (a battery supply critical mineral for which China currently controls the European supply chain, creating a need for European governments to foster supply chain ‘diversity’).

- Tier 1 jurisdiction status (not yet) – Unlike Canada, Greenland is not yet formerly considered a Tier 1 mining jurisdiction (i.e. having ‘premium’ mining law and regulations, political stability, strong legal system and infrastructure). However, Greenland’s government, which has a high degree of autonomy from Denmark, is working hard to improve consistency and effectiveness of mining legislation. There is evidence to suggest that Greenland licences can be awarded by the Mineral Licensing and Safety Authority (MLSA) within 3 months, from registration to completion of the application (MLSA, 2023).

- REEs – Greenland’s main REE deposit, Kvanefjeld, also has potential for uranium production. However, the exploration of uranium deposits with a concentration higher than 100 parts per million (ppm) has been banned in Greenland since Nov 2021 (World-nuclear, 2023). This relatively new law was passed due to concerns around the environmental impact of uranium mining in Greenland. This was disruptive for investors already committed to the Greenland mineral exploration market and no doubt put off other investors. Nevertheless the uranium legislation could open the door to a different type of investor, i.e. those with a keen focus on ESG and sustainability.

- Politics – A challenge for investors (and so miners) is that Greenland’s ~57k nationals are trying to navigate the tricky pathway between sustainability, environmental preservation and monetizing its rich mineral resources. This has inevitably resulted in changes of step and direction in mining policy, which has left investors with the impression that Greenland is a somewhat uncertain jurisdiction and so difficult investment opportunity – indications are that this is changing for the better.

- Greenland Mineral Resources Portal (Greenmin) – The portal provides easy access to the geology of Greenland, its mineral resources, and geophysical data. It serves as a comprehensive resource for industry professionals, researchers, the general public, retail and institutional investors, who are interested in exploring and understanding the mineral potential of Greenland. The portal aims to promote transparency, facilitate informed decision-making, and support sustainable development of the mineral sector.

Greenland’s potential – world class analogues (e.g. Canadian resources opportunities)

Critical raw materials are central to the energy transition wave, digitisation, alloy development, gas turbine and aircraft jet engines, electronics and a range of other technological developments. Mining critical minerals can be challenging and mine development can be relatively slow (depending on the minerals and the geography).

Investors sometimes cite that Greenland is inexperienced when it comes to mineral resource monetization. Whilst there is some recent truth in this concern, Greenland has a long history of mining, including the world’s largest mined source of Aluminium.

In 2000 Greenland hit the headlines as a vast largely untapped mineral resource especially due to the abundance of ‘the critical 38’ and the country’s pro-mining stance. However, misperceptions of Greenland’s remoteness, extreme climate conditions, lack of infrastructure and legislative and investor relations missteps took the heat out of investor interest.

Potential for tax regime change – Greenland’s high tax rate in relation to minerals royalties also dampened investor enthusiasm – 5.5% gross royalties on gemstones, 5% on REE and 2.5% on other minerals does not seem exorbitant. However there are other tax burdens for miners and they soon stack up – a ‘surplus royalty’ for over 40% profits (the royalty is calculated as a share of the exploration licensee’s profits and the tax rates are 3.75%, 8.75% and 15%). Again one may argue this is not entirely unreasonable. The challenge is that the tax regime removes the cushion against commodity price volatility (Trade Commissioner, 2023).

You can’t beat a person who never gives up – Investors with a long view and toughened stomachs have not been put off – is it because the opportunity is, in the end, just too attractive not to have exposure to? The opportunity is certainly supported by structural economic fundamentals and the demand schedule for what Greenland can offer in terms or mineralisation (it is broadly accepted) is only going to get tighter.

Some instruments to consider for investment exposure

- Amaroq Minerals (TSXV: AMRQ, LSE: AMRQ.L) – The largest licence holder in Greenland after being awarded two further mineral exploration licences in South Greenland in Dec 2023. Total land package is 9,785.56km2.

- Premium Nickel Resources (TSXV: PNRL) – Its Maniitsoq project at the 3,048km2 Maniitsoq property is 100% owned. It focuses on high-grade nickel-copper-cobalt-precious metal sulphide within the Greenland Norite Belt (GNB) and close to Seqi deep water port/Seqi Harbor (Premium Nickel Resources, 2024).

- Greenland Resources (OTCPNK: GRLRF) – Is focused on molybdenum (Mo) within its flagship project called Malmbjerg (an open pit pure Mo exploration project) which is supported by the European Raw Materials Alliance (ERMA). The project is located in East-Central Greenland and 20km from Mestersvig airport (while not Greenland’s main airport, it primarily supports mining and scientific research activities providing logistical support).

- Hudson Resources (TSXV: HUD.V) – Focuses on critical green mineral projects in Greenland with Gronne Bjerg Anorthosite project (100% owned) on open tide water near the capital of Nuuk (Hudson Resources, 2024).

- GreenRoc Mining (LSE: GROC) – Its flagship project Amitsoq Graphite is located in southern Greenland and has among the highest-grade graphite deposits globally, with a JORC Resource of 23.05m tonnes at an average grade of 20.41% graphitic carbon.

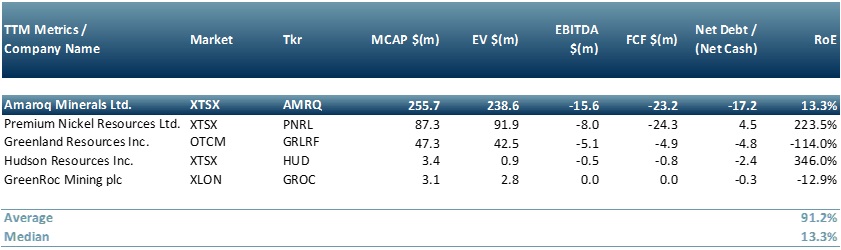

Exhibit 2 – Peer group table of the above-mentioned mining companies with projects in Greenland

Sources: ACF Equity Research Graphics; Refinitiv.

In spite of Greenland’s relatively low profile at the moment in terms of mineral exploitation opportunities, the world’s most powerful regions remain strongly interested in Greenland’s mineral potential.

Among these powerful players are the European Union, Canada, US, Russia and China – the latter three are actively competing for Arctic resources (BBC, 2020).

Greenland continues to represent an extraordinary opportunity and the timing may not get any better for the west – notwithstanding US president Donald Trump’s seemingly comical offer to buy Greenland and China’s investment in Greenland is somewhat reduced because of local (Greenland) opposition. Russia is currently persona non-grata in Greenland because of Greenland’s attachment to Denmark (a full NATO member) – whilst not a formal member of NATO Greenland enjoys NATO’s security umbrella. Greenland also hosts the US’s Thule Air Base (referred to as Pitfuffik Space Base).

In the end no one can ignore artic minerals (exploring/extracting/processing/purchasing). Greenland is by far the most practical and most sustainable opportunity.