Activist ESG funds – smaller firms on the radar

Activist funds are making a comeback after a retrenchment in 2020 due to Covid-19. Smaller companies are particularly vulnerable.

The resurgence in activist strategies and the growth in new players in this space is driven by two factors – sustainability/ESG and a frustration with passive investment strategies.

In companies above $500m MCAP activist campaigns often raise legitimate concerns, but they tend to destroy Total Shareholder Return (TSR) for 12 months. 50% of CEOs subject to an activist campaign end up moving roles, according to data presented by Boston Consulting Group (BSG).

The number of new players in the activist space is likely to account for greater than 30% of all campaigns.

All the indications are that activist fund management is accelerating rapidly as an investment strategy.

One of the issues for passive managers is that they do not carry out due diligence and though sustainability / ESG does raise EVA that is only true for companies that embrace the internal disciplines created by an ESG with public metrics.

The passive strategy has turned out to be less than a good idea when it comes to reducing longer run ‘lethal’ risks because of the lack of verification.

For now, sustainable investing is more or less impossible to execute effectively via a passive investment strategy because of the lack of standard or consistent assessment processes available for ESG ranking.

The new wave of activist investors are pushing forward the ESG agenda. While activist funds tend to target large-cap companies, smaller companies are also on their radar.

Key points:

- Activist funds purchase shares of companies in order to effect a significant change in the company while advancing their investor agenda – e.g. targeting environmental and social issues.

- Some consider the role of activists as all smoke and mirrors – Trian Partners took a US$ 2.5bn stock position in General Electric (NYSE: $GE) in 2015 and any significant outcome of its campaign is yet to be seen.

- While the pandemic temporarily reduced the number of activist campaigns during 2020 – two global trends suggest a rebound – frustration with certain aspects of passive investments (funds that track an index and not an individual stock and carry out nil verification or due diligence) and ESG / sustainability, itself driven in large part by both climate and social change data.

Historical background to activist portfolio management – it is older than you might think

Shareholder activism dates back to 17th-century Dutch republic and Isaac Le Maire – major shareholder of the Dutch East India Company (VOC – Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie) and the father of short-selling.

At the time, early corporations were already implementing some form of corporate governance, e.g. voting rights, dividend payments, press coverage charters and bylaws. The phrase ‘Corporate Governance’ was coined in 1976 by the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).

Activist campaigns first found ground in the US and have since expanded to other regions, EU & UK (exhibit 1). The number of campaigns increased to ~797 in 2020E vs. 484 in 2017A (Harvard Law, 2020), with an unsuccessful rate of 53% and 34% respectively.

The reason for the unsuccessful rates cited above is that campaigns bring negative publicity, they are time consuming and can also disrupt daily business activities.

How it works – activist tactics

The activist approach uses an equity stake in a company in order to put pressure on management to adopt or change policies to one that the activist believes will deliver superior returns for its shareholders. e.g. sustainability/ESG with metrics.

The activist fund achieves change in most cases by winning a seat or seats on the board, installing a new executive team or forcing a corporate restructuring (incl. selling underperforming business units).

Activists, in the experience of our team working with activist targeted companies, generally take one of two general approaches to secure board representation:

- a) activists either build a percentage shareholding (5% or more) that entitles the activist to one or more board seats or;

- b) engage in a battle using proxy challenges (corralling other shareholders to vote for its cause) and assembling damaging cases against the board or individual board members that the activist offers to make public, if the board does not accept the activist’s proposed board appointee(s).

The strategies above, a) and b), are why smaller companies are so much more vulnerable. Smaller companies’ shares are easier to force down and their management teams often lack the personal and financial resources to mount an effective defence.

The TSR damage is far greater because the proportionate amount of distraction for the executive team is so much more and…all things being equal…the probability of the founder or CEO losing his or her role is also much greater compared with corporates above $500m MCAP.

- Engine No.1 is an activist fund based in San Francisco established in 2020. The fund has three directors on the board of ExxonMobil (NYSE: $XOM) while it only has a 0.02% stake in $XOM.

Engine No.1 was able to get on the board by driving, and corralling the support of much larger portfolio managers, including Blackrock and State Street, by proposing the argument that Exxon is failing to prepare for a clean-energy future, i.e. transitioning away from fossil fuels.

- Bluebell Capital Partners (another new activist firm) co-founder Giuseppe Bivona says “ESG cannot be an excuse for a company to underperform.” Our own research suggests a strong position statement – ESG is a driver for outperformance (at least whilst it is a stock differentiator).

Activist Fund/Investor/Shareholder – friend or foe?

Hedge funds with an ESG/sustainability agenda are adopting activist tools and strategies. Hedge funds trade in mostly liquid assets to allow for tactical and strategic flexibility, which is at the heart of their superior returns delivery.

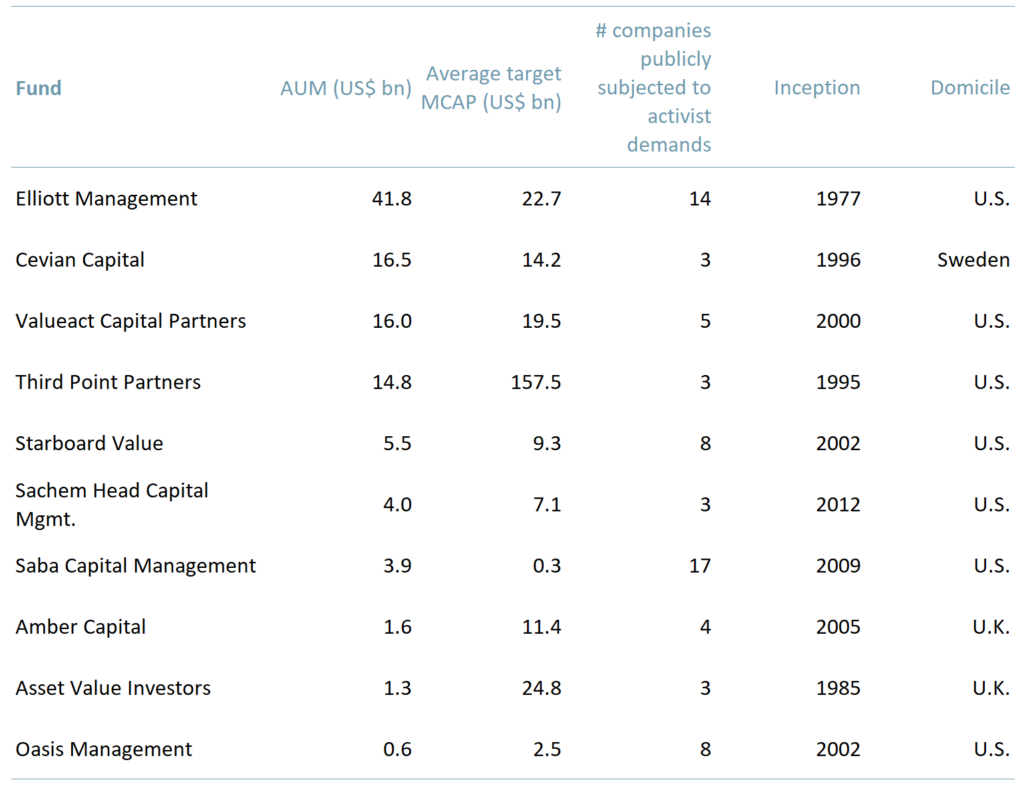

Exhibit 1 – Top 10 activist funds by AUMs 2021

Sources: ACF Equity Research Graphics; Activist Insight; company websites

Sources: ACF Equity Research Graphics; Activist Insight; company websites

Activist entities target large companies but also small corporations. The impact of these campaigns on a large cap company is far from minimal, and for a small-cap the impact is proportionately greater.

Activists come on strong and in the Engine No. 1 example above, the activist was perfectly able to harm the reputation of Exxon’s management team in order to achieve its strategic goals.

The damage is not just to reputations, activist campaigns also disrupt business operations. Smaller companies tend to have smaller teams and proportionately less financial resources. Any disruption severely affects operations and in turn profitability and investor interest.

On the other hand, the stake that activist investors take in a company is generally relatively small, as per the Engine No. 1 example, in which the portfolio manager only holds 0.02% of $XOM. However, make no mistake – the stake may be small, but the impact is big. So how does having such a small stake in a company translate into a significant influence, i.e., three board seats?

The significance of owning a very small stake (%) in a company

In most cases, investors will hold a minority stake in a company. Ordinarily, portfolio manager and individual investors have very little influence on the company itself.

Most company boards believe they have little to worry about in practice below a single entity holding of 50% plus one share, which equals legal control and a majority interest.

ExxonMobil ($XOM), MCAP ~ US$260bn, is the world’s largest publicly traded oil & gas company. For a company of its size, its major shareholders (i.e. institutions) all own less than 10% – there are no majority interests in the company.

Therefore, for Engine No.1 to secure three seats on the board with just 0.02% stake was unprecedented – it was made possible by the increase in the importance of ESG / sustainability to investors and capital markets.

Engine No.1’s stake may have been small but it in respect of business strategy decisions it amounted to control.

Engine No.1 is a portfolio manager, but it is not unheard of for a single individual to purchase over 10% of the shares in a large-cap company.

In June 2021, telecoms billionaire Patrick Drahi purchased 12.1% of the UK’s dominant fixed line telco, BT ($BT.L) – the equivalent of £2.2bn (~US$ 3.1bn).

Drahi created Altice UK for the sole purpose of holding the $BT.L stake and claims that he does not intend to use his stake to launch a takeover bid for BT (Altice is owned by Next Alt which also owns SFR (Société française du radiotéléphone) – the second largest telco in France after Orange).

Drahi is also thought to be aligned with Deutsche Telekom (DTE.DE), Germany’s dominant Telco, which itself holds 12% of BT and has well signposted acquisition ambitions.

If DTE were to bid for BT, Drahi could easily side with DTE without any breach of UK takeover rules. It is, essentially, a carrot and stick approach by Drahi to manage BT’s strategy.

Notwithstanding Drahi’s claims of being in the background, the City of London fears this is shareholder activism by the back door. According to JP Morgan (NYSE:JPM) analysts, Drahi is “unlikely to be satisfied by ‘modest’ double-digit return on his investment in BT.”

The Drahis of this world are small in number, but there is nothing to stop an individual with a few million dollars executing the same game play on a smaller company – having a dominant retail investors base is not a defence – reddit vs. Gamestop (NYSE:GMS) AMC Entertainment (NYSE:AM) etc.

ESG activism

Engine No. 1 bought into $XOM at an opportune time. At a time where all classes of investors including the larger portfolio managers (Blackrock, Vanguard, Stat Street, etc. who own shares of Exxon) are pushing the ESG agenda and seeking to make ESG reporting mandatory. Therefore, it was no surprise that these majors supported the election of at least two of Engine No 1’s candidates.

As a green boom emerges, investors are scrutinizing the effect that companies have on the climate and along with regulators, politicians and the courts, are turning a sharp carnivorous eye on greenwashing, which is again on the rise. Investors view corporate attention to ESG criteria as closely linked to business resilience, competitive advantage, financial performance and so investor returns.

Investors, institutional and retail, continue to support ESG-themed proposals while lobbying governments and regulators, e.g. the US the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Investors continue to do so because regulatory authorities are not acting quickly enough and ESG with public metrics improves EVA. Not focussing on ESG is now seen as damaging to investor returns.

Corporates may choose to wait for progress from governments and regulatory organisations in standardising ESG reporting requirements, but the markets are already two steps ahead. ESG is here and it is very real. Waiting for regs to implement a policy can only delay investment opportunity prospects. Activists are not waiting for corporates to get organised, rather they are looking for the weaknesses.

The key to defence, as is so often the case in life, is offence – which means a corporate must get its valuation message out to stake holders as compellingly, cogently and as often and as possible.

Smaller public company owners and executive management teams must expect opportunistic activist attacks and arrange their defences. Not doing so does not end well for management teams.

Authors: Renas Sidahmed and Christopher Nicholson – Renas is a Staff Analyst and part of the Sales & Strategy team and Christopher is MD and Head of Research at ACF Equity Research. See their profiles here

![Climate change and the [re]emergence of millet Climate change and the [re]emergence of millet](https://acfequityresearch.com/wp-content/webpc-passthru.php?src=https://acfequityresearch.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/ACF_Millet-a-new-sustainable-market-_Twitter-470x320.jpg&nocache=1)