Are SPACs a good option for investors?

SPACs (Special Purpose Acquisition Company), also referred to as Cash Shells on the UK’s junior markets, have become very popular over the last year. As rules tighten and the pool of companies wanting to go public gets smaller, will the SPAC trend fade? Has the SPAC vehicle lost most of its credibility and should it be shunned, at least in the US?

Key Points:

- A SPAC is a corporate vehicle with no operations but with cash raised from investors that sets out a particular goal or philosophy to explain to investors what it will do with the cash it is raising, or has raised, from those investors. A SPAC is a higher risk vehicle than a company with operations, by definition.

- After listing on the stock market SPACs often require more funding to complete the acquisition of a private company.

- This source of secondary financing for blank cheque companies is known as PIPe (Private Investment in Public equity) finance and is becoming much harder to source.

- PIPe investing is illiquid with funding sometimes / often tied up in the blank-cheque company for years.

- With more blank-cheque companies on the market than ever before, PIPe investors are looking for companies with high quality target acquisition list at good prices (as are we all).

SPACS, are a type of blank-cheque company that has no assets other than cash raised through an ‘IPO’ and secondary post-IPO PIPe financing rounds. The money raised at IPO is used, alongside the PIPe secondary financings, to complete the merger or acquisition of a private company, known as an initial business combination (IBC) taking the private target company public and avoiding the traditional IPO process.

The traditional IPO process is expensive, time consuming and risky in so far as a corporate may not get regulatory clearance or raise the amount of capital it was targeting at the price it hoped for.

The most significant advantages for private companies that choose to reverse into being acquired by SPACs in order to go public are as follows:

- Cost: SPACs typically pay for most of the costs of the private company going public, avoiding the large fees.

- Time: The initial business combination typically takes 2-3 months vs perhaps 12 months or longer for an IPO process.

- Value: With SPAC deals the private company knows how much it will be receiving in new capital, unlike IPOs which could provide varying amounts depending on the market.

Between 2008 and the end of Mar 2021 there were ~1300 SPAC IPOs based in the US, Canada, Italy and South Korea. Of the ~1300 IPOs, ~50% were listed on US exchanges. (S&P, 2021)

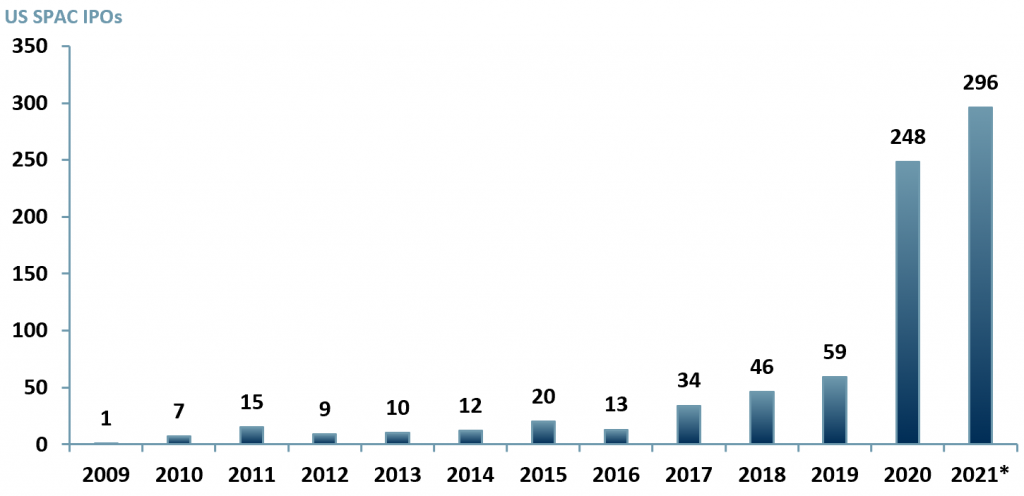

SPACs have been growing in popularity over the last 10 years. However, 2020 and 2021 have delivered much higher volumes of SPAC IPOs than in previous years with the number of SPAC IPOs in the US already exceeding the YE20 number in 1Q21 alone (exhibit 1).

Exhibit 1 – SPAC IPOs in the US 2009 – 2021

Sources: ACF Equity Research Estimates; Fortune Business Insights; Note: 2021 data only represents 1Q21 up to 29 March 2021

Sources: ACF Equity Research Estimates; Fortune Business Insights; Note: 2021 data only represents 1Q21 up to 29 March 2021

With so many SPACs now listed, not only is there more competition for PIPe finance but there is also competition to find enough potential targets (private companies) to take public. Of the SPACs listed in around the world since 2019, only ~25% have completed deals (Harvard Business Review).

SPACs are clearly useful for some companies, but do they benefit all retail investors? The most obvious advantage to retail investors is the right/ability to claim repayment of investment funds if the initial business combination is not completed within two years of the IPO. However, there are also some unique risks that come with a SPAC vehicle investment:

Trust account – This is an account which holds the SPAC IPO proceeds until the initial business combination. Upon closing of the initial business combination – the holder of the SPAC units may remain a shareholder in the ‘new company’ or receive their pro rata funds (see Pro rata share of trust account) back. SPACs generally invest the contents of the trust account in safe investments but there is no law requiring this, so investors must check the terms of the offering in case the trust account is itself used to make high risk investments.

Pro rata share of trust account – If an investor purchases SPAC shares on the open market, the investor is only entitled to a pro rata share of the trust account. This means if the SPAC IPO share price was $10 and an investor paid $13 three months later the investor is only entitled to $10 of the trust account should the SPAC not complete its initial business combination (SEC, 2021). This makes paying a premium for a SPAC share in secondary trading relatively unattractive, in our view.

Celebrity endorsements – There are now many celebrities encouraging investors to buy into certain SPACs. In March the SEC warned not to invest on the basis of celebrity endorsements as they may not have the investors best interests at heart or may not fully understand what they are selling. (SEC, 2021). One of our concerns is that celebrity investors may appear to be investing themselves but may also receive various fees or elements of remuneration that essentially return their initial capital in full, plus a return.

Essentially celebrity investors may be taking zero risk and receiving instant gains in comparison to the investors they are, for all intent and purpose, marketing to. This relationship may not be sufficiently transparent or clear to other investors.

The celebrity endorser may not understand that this is grossly unfair and inappropriate (as well as potentially illegal under securities / investment law interpretations), but that is no defence of their actions and there is little doubt they should be held fully accountable.

Sponsors – Sponsors generally purchase shares of the SPAC at a significant discount than the price offered to investors. This means if time is running out on closing a deal, they may agree to an initial business combination (IBC) that would hit its IRR or hurdle rate but which would not work out well for investors. To be explicit…a sponsor pays $1.00 for its share, a business combination is presented that will return $1.20 in say, one month’s time – the sponsor says yes to the IBC. However, everyone else paid $1.30 for their shares, they all make an instant 10 cent loss, and not a 20% return.

In certain circumstances we believe SPACs can benefit both private companies wanting to go public and retail investors. However, these situations do not come often, and investors are much more likely to lose out than the company that goes public.

We expect regulators to continue to crack down on many areas related to SPACs from curbing extremely optimistic profit projections on target companies to scrutinising underwriter’s exposure to deals. The rules will undoubtedly get tighter but before that point retail investors must be especially cautious when considering investing in SPACs.

Authors: Sam Butcher, Christopher Nicholson – Sam is a Junior Staff Analyst at ACF Equity Research, Christopher is a founding executive, MD and Head of Research at ACF Equity Research. See their profiles here