Inflation – why it is so important to monitor

Why the inflation rate is so important to monitor

Inflation matters so much because its presence leads to a reduction in purchasing power – when prices are subject to inflation in an economy, each unit of currency buys less goods and services than it did prior to the inflation effect.

In simpler terms, think of it this way – at a 5% p.a. inflation rate a $100 basket of goods this year will cost $105 the following year, and in 10 years, the same basket will cost $163, essentially reducing purchasing power by more than 50% – you are more than 50% poorer if your income does not rise too.

Equity performance is less certain for equity investors; debt investors are potentially ‘stolen’ from, but borrowers face a lower real debt burden.

CPIs (Consumer Price Indices) assist in the comparison of the price change of goods and services to measure purchasing power and thus inflation.

Inflation has many effects – most of them not good

All aspects of an economy are affected by inflation: from consumer spending habits, investment returns, employment rates, government programs, tax policies, interest rates and bond yields.

Because inflation affects the value of a currency and spending power, consumer behaviour changes. One behaviour change example is stock piling – entities buy more now because the real cost in the future is less certain.

Some supermarkets stockpiled products last summer during the covid induced lockdowns to try and keep prices down, one grocer said it increased its inventory 50%.

Ironically stockpiling can trigger inflation because it creates distortions in the supply and demand clearing price and injects uncertainty into the market.

Key inflation drivers:

- Demand-pull inflation (when demand for certain goods and services is greater than the economy’s ability to supply) – stock piling can create this effect

- Cost-push inflation (when overall prices increase due to increases in energy, cost of wages and raw materials)

- Rising wages due to scarcity of skills (a specific version of demand-pull inflation)

- Increased money supply via bank reserves loans

- Increased money supply by printing more money – devaluation of the currency (i.e. printing more money than the value of the economy or some other standard measure)

- Policies and regulations – usually an unintentional consequence, but sometimes deliberate to achieve political or economic ends.

Inflation is also linked to the unemployment rate (wage inflation, the Phillips curve). Companies raise prices because demand is greater than supply. Short term, this growth spur can lower unemployment (companies hire more labour) and so push up wage costs across the economy.

In the US, where the inflation rate has reached a slightly concerning 6.2% in Oct21 (the largest increase in 30 years), the Federal Reserve is now focused on tightening monetary policy using market signalling.

Not all market participants think the Federal Reserve market signalling is helping the US or global economy.

Inflation makes equity investing more uncertain

A rise in inflation increases borrowing costs and input costs, essentially it decreases expectations of earning growth as companies and firms face higher expenditures such as energy costs, labour, material (commodity prices usually rise with inflation).

Employers have control over one of these inflated costs in general – labour costs. But if labour costs (wages) are held stagnant across the economy, that in turn reduces consumption (employees have less real disposable income to buy goods).

Overall stocks tend to react negatively to sudden and sharp inflation increases and investors may demand a higher return to compensate for the higher risks (or simply the effect of inflation).

The main problem however is that jumps in inflation suggest an acceleration factor and that creates uncertainty for investors – put in simple terms investors no longer know what to charge for their capital to get a fair or market return, so they begin to ‘overcharge’, that reduces investment and so economic growth.

Understanding inflation and its effects is crucial to investing because inflation can shrink the value of investment returns and the value of savings.

There are pros and cons to inflation regarding debt markets. Borrowers can pay lenders back with money that is devalued compared to when the loan was taken out. On the other hand, lenders’ income (coupon) buys less, as does their capital, when it is returned, unless the lending instrument is inflation linked.

Overall, debt markets tend to become less liquid and the real cost of debt rises through upwardly biased mispricing. Therefore, across the economy, fewer projects can return a margin and fewer projects means less economic growth.

Inflation reduces bond yields – this should be a problem

Rising inflation can cause the prices of long-term bonds to fall the most.

Since bond interest payments are pre-determined, their value is impacted by inflation. The longer the term of the bond, the higher the inflation risk.

Bond prices therefore rise when central bank interest rates fall and bond prices fall when central bank interest rates rise.

The expectation at the moment because of inflation and historically low central bank interest rates is that interest rates are bound to rise and sooner rather than later.

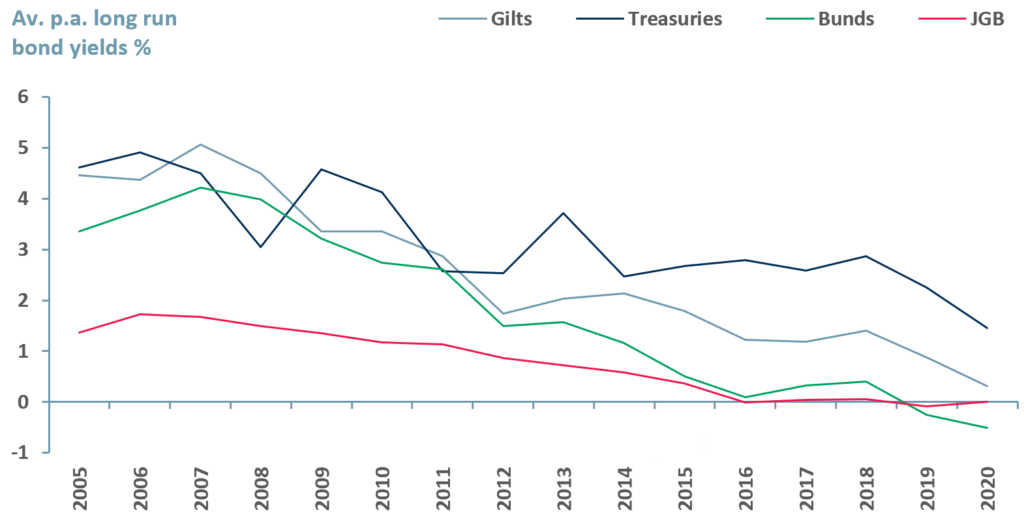

Exhibit 1 below shows long-term US treasury yields, gilts yields, Japanese government bond yields (JGB) and bunds yields from 2005 to 2020.

Exhibit 1 – Average-long run government bond yields in US, UK, Germany, and Japan 2005-2020

Sources: ACF Equity Research Graphics; ECB; Österreichische Nationalbank; Schweizerische Nationalbank; Norges Bank; Macrobond; US Department of the Treasury

Sources: ACF Equity Research Graphics; ECB; Österreichische Nationalbank; Schweizerische Nationalbank; Norges Bank; Macrobond; US Department of the Treasury

In 2000 UK gilts were at 5.33% by 2020 yields had fallen to 0.32%.

30-year US treasury bonds (T-bills) were at 4.81% in 2006 and decreased to 1.65% by 2020 (note that long run bonds have higher yields (ordinarily) than short run bond yields, e.g. one month bonds due to the risks of uncertainty of long-term maturity bonds).

In Japan, long-term JGB stood at 0% and dropped into negative territory in 2016 for the first time and in Germany, bunds declined from 5.26% to -0.51% by 2020.

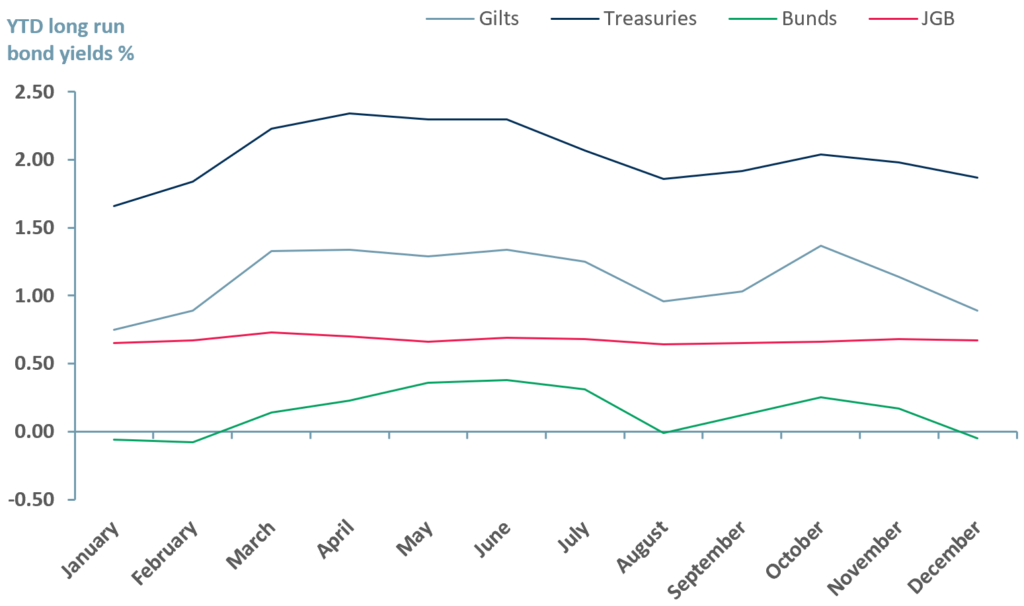

Exhibit 2 – YTD average long run government bond yields in US, UK, Germany, and Japan 2020-2021

Sources: ACF Equity Research Graphics; Federalreserve.gov; Marketwatch

Sources: ACF Equity Research Graphics; Federalreserve.gov; Marketwatch

When bond yields fall or go negative

A negative bond yield means that investors receive less money at the bond’s maturity than its actual par value, i.e. they get less capital back at maturity than was initially lent. However, investors that need income (pension fund managers) or whose other investments are in deeper negative territory (relative performance), still tend to buy negative yield bonds, at least in the short run.

When yields fall into negative territory, it results in lower borrowing costs for corporations and the government. All other things being equal, consumption increases, mortgage rates may decline too, along with a rise in housing demand, which are themselves all inflationary pressures, leading to even more negative real yield.

Bond market and inflation expectations

The behaviour of bond markets is determined by inflation expectations and central bank interest rate responses to those inflation expectations.

To combat the effects of negative yields, interest rates have to rise, and higher interest rates slow or reverse economic growth. Inflation is therefore hard to manage and the cure is painful and often prolonged if inflation expectations move from short run to long run.

Investment opportunities in period of high inflation

Equities – During periods of relatively high or high inflation value stocks such as food, energy and property usually do well and equities, such as miners and oil gas, benefitting from higher commodity prices can also flourish.

Commodities – Investment instruments considered as hedged against inflation are commodities such as grains, precious metals (gold is considered a store of monetary value), natural gas, oil, beef, orange juice.

FX – some foreign currencies – e.g. the Swiss Franc has characteristics at this time that might mean it proves to be a good inflation hedge.

Bonds – treasury inflation protected security (TIPS) may turn out to be hedges against inflation – it is certainly the point of the instruments so that governments can continue to borrow even during periods of relatively high inflation.