Pricing nature & carbon credits

IMF Assistant Director in ICD developed a pricing mechanism for carbon sequestration four years ago by appraising natural resources. The expansion of carbon credits could save the ecosystem.

- Carbon sequestration is a natural or artificial process that captures carbon from the atmosphere and slows/reverses the amount of CO2 atmospheric pollution.

- In nature, elephants, whales, mangroves and seagrass salt marshes are all ‘nature-based solutions’ that capture carbon with no side effects.

- Elephants encourage the growth of slow-growing trees by knocking down, eating and stomping on fast-growing trees. In doing so, this helps forests store more carbon in the trees and not the atmosphere (trees suck up carbon dioxide when they photosynthesize, which gets repurposed into their trunks, branches and roots).

- The counterintuitive reason for slow growing trees sequestering more carbon runs as follows – in absolute terms fast growing trees tend to be young. Slow growing trees tend to be old. A 100cm trunk diameter tree adds 10 kg to 200 kg above ground dry mass p.a. (species dependent). This is 3x the rate p.a. that 50cm diameter tree adds mass and is the equivalent of the above ground mass of a 10-20cm tree p.a. So though the rate of growth is slower in old trees the total mass of carbon sequestered by older trees is greater p.a.. Source: Nature 507 90-93(2014) N.L. Stephenson, A.J. Das, M.A. Zavala Jan 2014, Rate of tree carbon accumulation increases continuously with tree size.

- The movement of elephants is said to increase carbon sequestration by 6-7%.

The ‘win-win’ model

- Ralph Chami’s, IMF ICD MD, model prices natural resources and then sells the services, i.e. carbon sequestration. Companies will not own the natural resource outright, that belongs to the host country.

- Chami’s model values a forest elephant in carbon sequestration at US$ 1.75m over its entire lifetime, which is the equivalent of 9,500 tons of CO2 captured.

- If, for example, a company buys the services of elephants in Ghana, the elephants still belong to Ghana as to do the forests. In turn, a company is then able to write down its carbon sequestration/carbon emission cost.

- The funds used to purchase the proposed service would go to the local community. This would incentivize the community and local potential poachers to look after the elephants and their natural habitat. The funds would provide these local communities with employment, steady income, and a cleaner and greener environment.

- Governments would also benefit from this expansion of the consumption base as employment will increase as new businesses are formed. This stimulates the economy and promotes long-term growth for the population, the animals and the ecosystem.

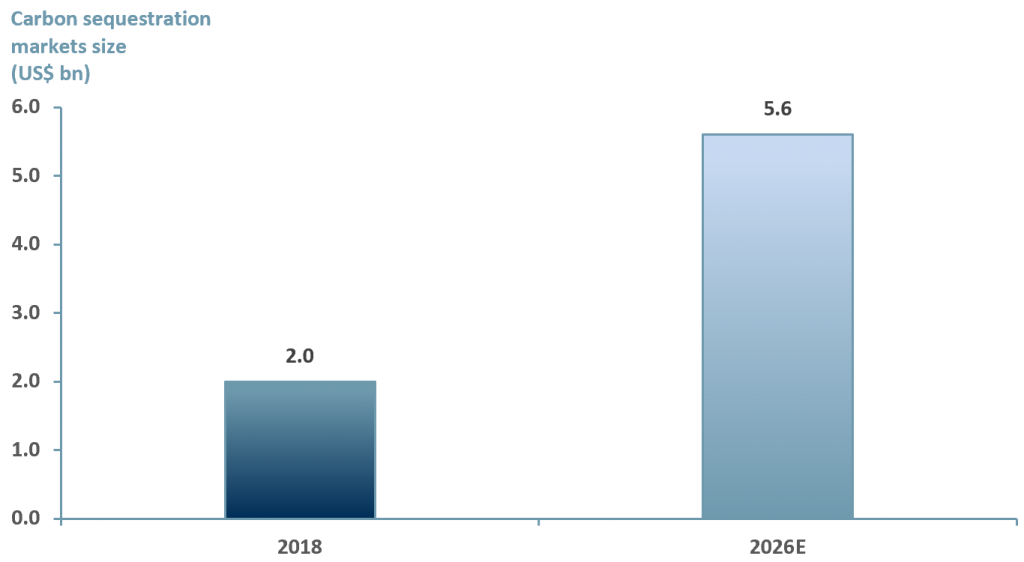

In exhibit 1 below, we show the total value of the carbon capture and sequestration (CCS) market for 2018A and 2026E. According to a survey carried out by Fortune Business Insights, the market will reach US$ 5.6bn in 2026, up from US$ 2bn in 2018, an increase of 180%

Exhibit 1 – Global carbon capture and sequestration market 2018 and 2026

Sources: ACF Equity Research Graphics; wallstreet-online.de; Fortune Business Insists

Sources: ACF Equity Research Graphics; wallstreet-online.de; Fortune Business Insists

The future of farming and carbon credits

According to Mr. Chami, if we (collectively) are to meet the Paris Agreement goals for 2050, we only have two options:

- Find, innovate, create new technology that allows companies to maintain their current business operations without producing any emissions at all. A similar approach is called for at the heart of Bill Gate’s foundation and in his recently published book ‘How to Avoid Climate Disaster’.

This is a highly unlikely and an unrealistic approach in the time available. We are not in opposition to Bill Gate’s central argument, we are just not as hopeful. Even if companies begin to make certain changes, it will take time. We are seeing this in the oil industry. Big oil is pulling out of the industry and diversifying its portfolio, but not quickly enough.

Energy sectors of major exchanges are dwindling as the globe moves to a green energy transition. For example, Exxon Mobil (NYSE:XOM) dropped out of the Dow Jones in August 2020, due to declining investor interest in its shares and so valuation.

- Find existing technology or processes that work towards offsetting current emissions and potentially reducing them significantly.

This is the more ideal solution because nature is already doing this for us. This has been observed in the herd-like behaviour of cattle when rotational grazing livestock is implemented.

Cattle herds in small groups and when grazing on native grass, not mono-crop corn, will produce less carbon emissions.

In addition, as they move from paddock to paddock, the high density of the herd and the little amount of time spent in the paddock, works effectively to build soil carbon (increasing the level of carbon in the soil while decreasing the level of carbon in the atmosphere).

Rotational farming has been around for centuries and has significant benefits on improving the quality of soil and reducing pollution. As little as 30 years ago UK farmers would not have given a second thought to anything except rotational farming. Innovations from the agro-business sector changed this approach (pesticides, fertilizers, machinery). On the other hand, the initial upfront costs to farmers to change back to rotational systems are relatively high and deliver lower margins in the short term and maybe the long term too.

Rotational farming requires crop diversification, which in turn requires an investment in different types of machinery – i.e. a higher upfront capital cost. How to mitigate those risks for farmers? The answer is carbon credits.

Incentives such as Chami’s model and other companies’ efforts such as Regen Network (a US based company that buys and sells ecosystems) are the way forward.

Regen Network provides farmers involved crop rotation, rotational grazing, etc. with an opportunity to earn compensation for services provided that protect our ecosystem. In turn, the buyers/companies are able to purchase ‘credits’ and as explained previously, write down their carbon emissions.

The small company incentive

Protecting our ecosystem is not only a collective effort but also a creative and strategic effort.

We maintain a level of realism/pessimism about the rate of innovation in this area – which is that carbon emissions are not going to disappear overnight and we are not going to adopt, en masse, a carbon emissions free way to manufacture concrete/steel/glass tomorrow. However, there are options to offset these emissions in the meantime.

But what does this mean for nano to smaller companies? What does this mean for companies whose business models don’t necessarily emit a significant amount of carbon? How can they get involved?

Purchasing carbon credits is one solution. By investing in our ecosystem they are showing investors that they are taking the initiative towards a greener future. This is the era of the sustainable investor.

ESG and sustainability is on everyone’s agenda and thanks to Covid it will continue to remain the topic of conversation in the long-term. There is no getting around it.

Investors want to see that a company has an ESG policy. This drive is led by the large fund managers, e.g. BlackRock, State Street and Vanguard, but it has filtered through to retail investors as a desire and millennials seem inclined to accept nothing less.

Author: Renas Sidahmed – Renas is a Staff Analyst and part of the Sales & Strategy team at ACF Equity Research. See Renas’s profile here