Researchers say that our pain threshold can be linked to Neanderthal DNA

Researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology (Germany) and the Karolinska Institutet (Sweden) say that our pain threshold can be linked to Neanderthal DNA.

Neanderthals, or Homo neanderthalensis, lived in Eurasia up until 40,000 years ago. Current thinking is not that they went extinct, but that they were ‘absorbed’ by modern humans, which is a compelling explanation as to why many of us today are part Neanderthal.

The Max Planck researchers studied more than 362,000 questionnaires from the UK. The results were then compared to each individual respondent’s gene profile.

Gene profiling or gene expression profiling measures the behaviour of thousands of genes in order to determine how cells are structured and how they function.

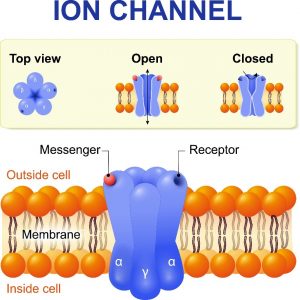

How cells function helps us determine whether or not they are behaving as ‘normal’ or if there might be some kind of change related to DNA or the environment. When examining pain thresholds at the biochemical level, researchers are interested in the behaviour of ion channels (gates through the cell membrane).

In the case of pain, ions pass through the cell membrane ion channels causing a change in cell chemistry that causes the firing of electrical impulses that we then experience as pain.

Ion channels are essentially a cell’s pore-forming protein gate that allow ions to pass in and out of the cell via the channel pore that spans the cell membrane.

The researchers observed that individuals with a low pain threshold had the Neanderthal ion channel variant. The Neanderthal variant contains three amino acids on the cell membrane that differ from the modern human’s cell membrane.

The amino acids determine which ions are allowed to enter and exit the cell membrane. In this case, the ion flow is imbalanced which is what triggers a pain signal.

This is a break-through discovery. It could help drug developers and offer patients a more precise/be-spoke treatment plan.

Hugo Zeberg, a researcher from the Max Plank Institute, says that we already know that some people metabolise drugs faster than others. He hopes that doctors will start taking into consideration the differences between patients. As with companies, businesses, products, etc., human beings are not a ‘one size fits all’ model.

This raises another important point – the drugs currently prescribed are not necessarily effective for everyone. Even the dosages prescribed do not have the same effect on individual patients. There is an increasing drive to get from the theory of personalised patient care to the actuality.

The healthcare industry is entering a new wave of increased R&D for alternative treatments as it prepares to navigate a post-Covid next normal world. Let’s hope it finally includes broadly available bespoke or at least semi-bespoke/individualised medicine. The trick is doing this profitably or if you are government, cost effectively. The opportunity remains vast, as do the benefits for all parties.