Smooth sailing over for water utilities

The UK Environment Agency’s 2020 annual report showcased “consistently unacceptable” environmental targets from leading water and sewage companies – Southern Water and South West Water.

The Environmental Performance Report singles out companies showing lack of transparency and initiative in fighting climate change and safeguarding the environment.

- Southern Water was fined £90m after pleading guilty to ~7,000 unlawful discharges of pollution between 2010 and 2015. Thames Water was fined £4m and £2.3m for separate sewage leaks. The problem with the fines is that the companies act in practice as if they essentially consider the fines no more than a cost to play.

- Eleven companies provide water and sewerage services in England and Wales. The Environment Agency (EA), the regulator for all waste management activities, works with these water companies to minimise the impact that their activities have on the environment.

- Despite some environmental improvements from Wessex Water, United Utilities ($UU.L) and Severn Trent Water ($SVT.L), most failed to meet all the environmental targets set out by the EA.

- The EA said that significant pollution incidents (i.e. intentional or unintentional release of harmful substances into the water, air or land causing environmental harm) in England had declined – there were 443 incidents reported in 2019-20 vs. 520 y/y, a 15% decrease. It is worth considering whether lower economic activity during Covid correlates with lower environmental harm incidents.

- Emma Howard Boyd (chair of the EA) says that companies are still “reaching for excuses rather than taking action”. To which we would say, make the fines have a significant impact on dividend pay-out resources. If institutions feel the fines in their pockets, and senior managers feel they could be forced out of their roles, this is more likely to achieve significant changes in behaviour, faster.

The UK water industry

There are 32 privately-owned companies that provide water, sanitation and drainage services (Ofwat). There are an additional three large publicly listed companies (Exhibit 2).

The industry was privatised in 1989. Prior to 1973 water & sanitation services were provided by water undertakings (i.e. companies) and sewerage disposal authorities. From 1973-1989 following the Water Act 1973, the UK government established 10 regional water authorities.

Privatisation of the water industry brought with it a regulatory framework embodied by a new organisation – OFWAT (Water Services Regulation Authority).

OFWAT was created to protect the interests of consumers and secure long-term and sustainable water supply and wastewater systems in England and Wales. While OFWAT is responsible for economic regulation of the industry, a government department, the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA), sets the policies.

DEFRA is the government department est. in 2001 that is responsible for the UK’s water and sewerage policy framework. This includes standard setting, drafting legislation and special permits (e.g. drought orders).

The EA on the other hand is a non-departmental public body est. in 1995 sponsored by DEFRA. Its role is to protect the environment in England only. (It oversaw Wales up until 2013, after which Wales created its own EA ‘chapter’).

Water – a dwindling resource, but it can be sustained

Water, along with air, is one of the most important resources on Planet Earth, covering 70% of the planet. However, its fresh or ‘usable’ supply for living beings is limited to just 3% – all the more reason why regulatory protection is needed.

Of the 3% of planetary fresh water <1 percentage point is available to humans. According to the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) ~1.1bn people lack access to water (14% of the total pop). Inadequate sanitation remains a problem for 2.4bn people.

There are rising concerns that droughts and increased pollution will:

- reduce the fresh water available to humans further and;

- increase the total population without adequate access to water and sanitation.

The EA, in a report in 2018, indicated that England is at risk of a water supply shortage by 2050 – this is largely due to increasing water use and wastage. The report showed that enough usable water for ~20m people is lost every day through leakages in the supply system.

Leakages occur for several reasons – operational, the length of mains (pipework), age of infrastructure and where consumers are based (urban or rural). OFWAT has set commitments where leakages are expected to reduce by ~16% by 2025.

Plans are in place to prevent usable water leakages, as they have been for decades essentially.

What is perhaps more revealing is the state of the UK’s fresh water systems.

Data published in 2020 revealed that only ~14% of English rivers meet the minimum standards for good or better ecological status (i.e. a healthy aquatic system – plants, insects, and fish – that can naturally remove pollutants and filter harmful substances).

Pollutants in the water come from raw sewage discharges by water companies directly into rivers, chemicals and agricultural run-off (i.e. sediment, pesticides, faecal contaminants that are run-off into rivers from fields as a result of rainfall).

The Environment Agency’s report not only puts pressure on water and sewage utility companies to be more transparent but also to be accountable. There is an overarching need for regulatory agencies to monitor water companies more closely and, in our view, make fines business critical, if necessary.

Climate target deadlines are fast approaching. According to Christine McGourty (chief exec of Water UK – lobby group), governments and regulators need to be more involved. McGourty says they need to “work with the water industry” in allocating funds appropriately so that UK rivers can continue to be sustainable and provide water that is usable.

A lucrative investment case with a coming twist

The GMB – UK general trade union – carried out its own private investigation of nine privatised UK water company shareholders. They found that in just five years, the shareholders made ~£6.8bn, while 2.4bn litres of water was wasted due to leakages.

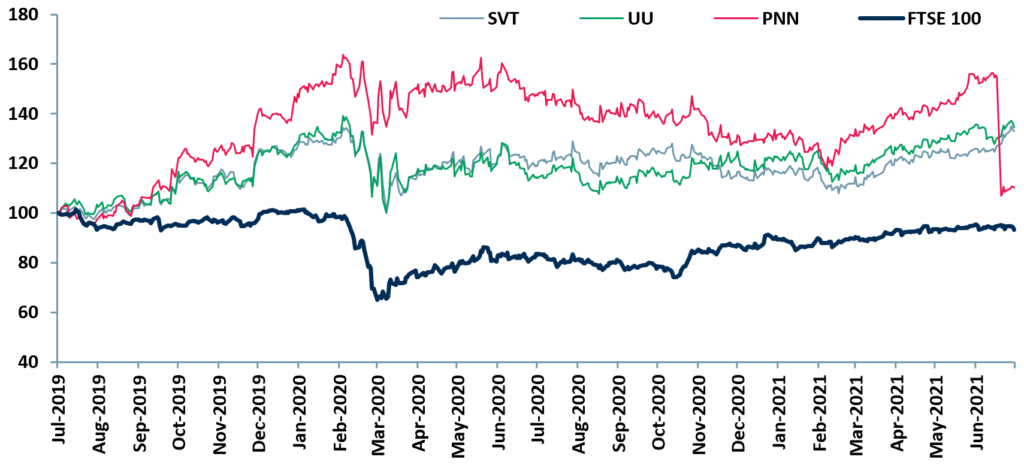

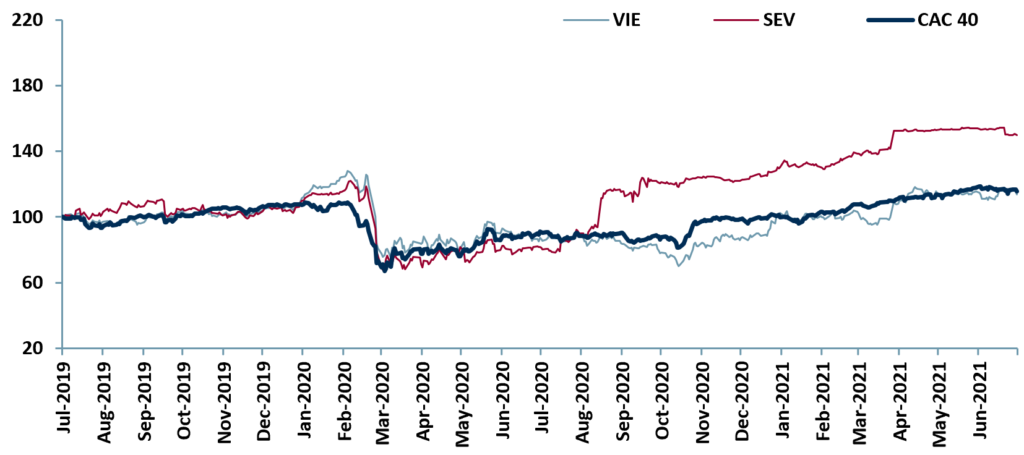

The water industry is a viable investment. In exhibits 1 and 2 we show how the public water companies in the UK and EU are outperforming the major indices. These include Severn Trent ($SVT.L), United Utilities ($UU.L), Pennon Group ($PNN.L), Veolia Environment ($VIE.PA) and Suez SA ($SEV.PA).

Exhibit 1– Price relative chart of UK water companies’ vs major index Jul 19 – Jul 21

Sources: ACF Equity Research Graphics; Refinitiv; Note: $PNN 05/07/2021 2:3 Stock Split and 355 Dividend

Sources: ACF Equity Research Graphics; Refinitiv; Note: $PNN 05/07/2021 2:3 Stock Split and 355 Dividend

Exhibit 2 – Price relative chart of EU Water companies’ vs major index Jul 19 – Jul 21

Sources: ACF Equity Research Graphics; Refinitiv

Sources: ACF Equity Research Graphics; Refinitiv

To implement the vital environmental improvements in the water industry, profits need redistribution or reallocation or companies must raise more debt and or equity to engage in large scale capital projects, fast.

Water (and utility) companies are able to pay-out higher dividends due to low elasticity of demand, so the risk of dividend or debt failure for investors is probably very close to the risk of sovereign default. But governments do not pay out anything like the degree of returns that utilities do to investors for a similar risk profile.

There is a clear utility company debt and equity pricing mismatch, underpinned by the free rider problem – water companies are not paying for the assets they use to generate returns to investors. In turn, this means that company managers and investors are not subject to the pressures that create financial rigour in other sectors – we forecast that will change.

Even during a recession, consumers and businesses are always going to need access to power, water, heat and telecommunication services. Given the needs of portfolio managers to service client pension obligations etc., the risk that utility companies will lose investor support is low during any part of the market cycle.

A study carried out by analysts at the Public Services International Research Unit at Greenwich University in 2018 showed that nine of England’s privatised companies had paid out dividends of £61bn over the 28 years since they were privatised, while accumulating debt of £51bn.

The data suggests that debt is raised largely to pay dividends rather than to invest in capital projects – this is not sustainable. It also suggests that both management teams and investors understand clearly that these companies will never be allowed to go bust due to their essential services characteristics.

These companies are under scrutiny for not actively tackling leakages and providing less than acceptable environmental targets. Sustainability (the “S” part of ESG), however, is not just a governmental agenda – it is now an overarching cause for concern in capital markets as well.

This push for sustainability also goes beyond corporates. Investors are more inclined to focus on companies with an ESG strategy in particular retail millennial investors. This class of investor is increasingly conscious of environmental issues and investing their wealth in line with best ESG practice.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, there has been huge global growth, both in interest and action, in respect of Environmental Social Governance (ESG). Reporting ESG metrics showcases a company’s efforts in enforcing a sustainable business model and best practices.

Investors are already demanding to see these changes; however, the general view is that sustainability is not a one-man show. Investors, corporates, governments and regulatory authorities all need to be collectively involved.

We do not agree with the general consensus – coordinating the above list of entities is simply not possible- there needs to be a leader. Capital markets have more influence than any government or regulator. Capital markets participants can change corporate behaviour…easily, they just need to conclude that the economic implications are significant enough to force change. In our assessment, capital markets are beginning to exert ESG change.

Exhibit 3 – Peer group table of UK/EU Water & Utilities companies

Source: ACF Equity Research Graphics; Exchange Rate: (Source: XE.com) EUR vs GBP: 0.8567

Source: ACF Equity Research Graphics; Exchange Rate: (Source: XE.com) EUR vs GBP: 0.8567

Authors: Anne Castagnede and Renas Sidahmed. Anne leads the Sales & Strategy Team; Renas is part of the Sales & Strategy and an Investment Research Teams at ACF Equity Research. See their profiles here

![Climate change and the [re]emergence of millet Climate change and the [re]emergence of millet](https://acfequityresearch.com/wp-content/webpc-passthru.php?src=https://acfequityresearch.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/ACF_Millet-a-new-sustainable-market-_Twitter-470x320.jpg&nocache=1)