Zinc’s unexpected supply squeeze

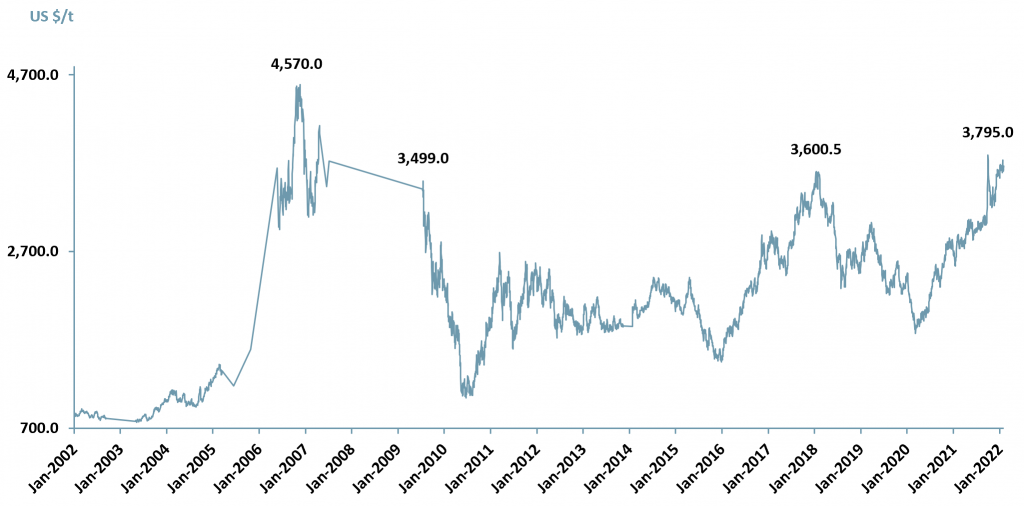

Zinc prices are approaching 20 year highs. Zinc’s price rise has caught many forecasters by surprise because they had expected market oversupply.

The World Bank’s Commodity Markets Outlook (October 2021) forecast a 4% decrease in the price of zinc to $2,822 per metric ton (MT) in 2022E from $2,950/MT in 2021E.

Furthermore, the price of zinc was forecast to decline to $2,200/MT by 2023E as zinc mining output gradually increased as a result of new mines coming on stream.

However, in 2021A zinc prices increased by 30% versus the previous year (exhibit 1) and zinc is currently trading between approximately US$ 3,500 – 4,000/MT.

Exhibit 1 – Zinc price movement 2002A–2022A

Sources: ACF Equity Research Graphics; Business Insider

Sources: ACF Equity Research Graphics; Business Insider

Why did markets get zinc price development so wrong in 2021 and 2022?

The current price development of zinc is driven by several competing factors:

- Zinc supplies, like all commodities, were disrupted due to the closure of mines as a result of Covid-19 restrictions;

- Ongoing environmental restrictions on mining in China have come to the fore. China is the largest producer of zinc, accounting for 35% of annual global output of 4.2m metric tons in 2021;

- Input costs (energy in particular) have risen steeply and rapidly over the last 12 months;

- Surpluses in zinc production in 2021 of around 400k tons (investingnews.com) caused Nyrstar (EBR: $NYR) – one of world’s top zinc smelters – to announce plans in Oct 2021 to cut production at its European smelter operations;

- Prior to the events of the last 24 months, markets had expected China’s zinc output to increase as a result of reinvestment and gradual modernization of its older zinc-smelting facilities.

Zinc and its applications

Zinc mining is conducted primarily underground, with ~80% of zinc extracted from subterranean ores. Zinc deposits most commonly manifest as three mineral types – zinc sulphide (ZnS), a ferrous blend called marmatite [(ZnFe)S] and calamine, which is zinc carbonate, ZnCO3(Britannica, 2020).

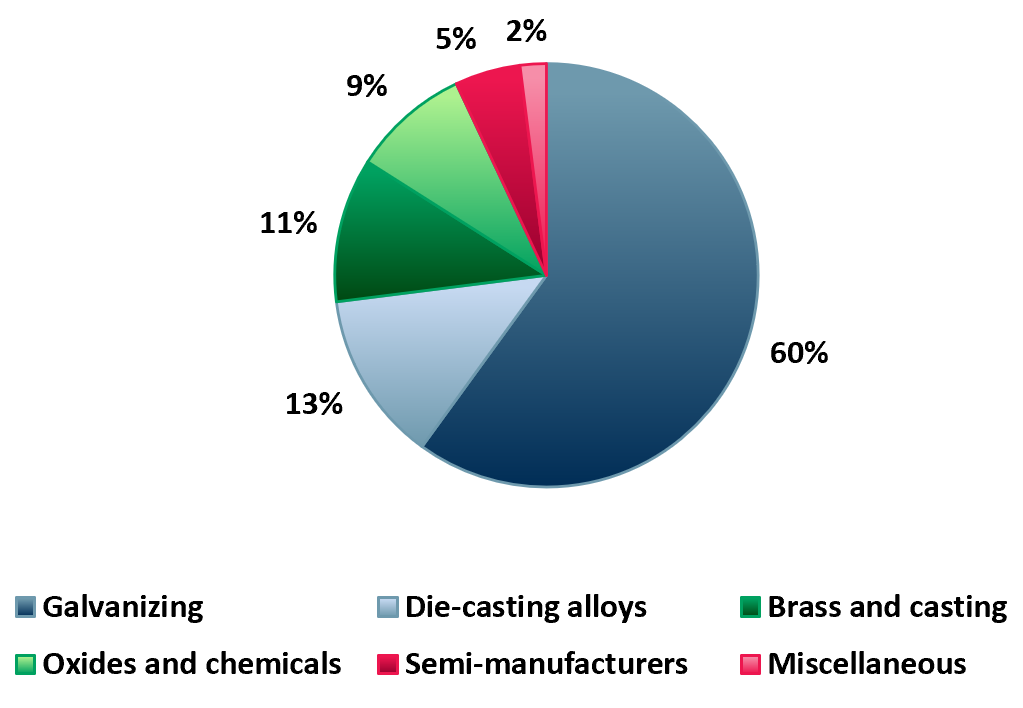

Zinc’s main use (60%) is in galvanizing – the process of coating iron or steel with a protective layer of zinc to prevent or delay oxidation of iron and steel (exhibit 2). Zinc is used in galvanising because it forms corrosion by-products that reduce the rate of corrosion in the underlying ferrous metals.

Galvanised steel is used in automotives (11kg of zinc per car), construction, shipbuilding industries, light industry, machinery, household electrical appliance and batteries (RSC, 2020).

Exhibit 2 –Zinc’s industrial usage 2020A

Sources: ACF Equity Research graphics; ChemAnalyst

Sources: ACF Equity Research graphics; ChemAnalyst

The second primary use of zinc is in die-casting alloys (13%). Die-casting is when molten nonferrous alloys are fed into dies (steel moulds) at high speeds and under high pressure. Zinc is used because of its high ductility. Examples of zinc alloys can be found in engine parts, musical instruments and household fixtures.

Zinc is becoming increasingly accepted at scale as a substitute-good for lithium in Lithium-ion batteries. The International Zinc Association (IZA) is optimistic regarding the potential for zinc-based batteries in the future of energy storage.

In 2020, the IZA launched its Zinc Battery Initiative promoting rechargeable zinc batteries. Zinc batteries are capable of long-duration storage and could work towards creating energy grids that are independent of extreme weather conditions.

The global economy transition to clean and renewable energy sources will drive demand growth for zinc.

Can long term zinc supply meet demand driven by the global renewable energy transition?

Tightened short-run zinc supply as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic has continued throughout 2022. Fitch Ratings forecasts suggest that ‘short-run zinc’ shortages could continue through to 2023, making shortages look more mid-term than short term.

The closure of European zinc smelters due to the energy crisis, has created a zinc price squeeze. As a result of the zinc price squeeze and a looming long-run/structural supply deficit, the US and EU are looking towards Asia for increased zinc imports.

Even if EU smelters were to reopen, a zinc price of $4,000/MT may not clear the market or even allow smelters to achieve breakeven. Zinc at $4,000/MT may not be enough to compensate for recent increased input costs, that now also look structural because of the Russia-Ukraine conflict.

ACF is of the view that markets entered a commodity supercycle in 2021. The pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine war have accentuated potential structural supply deficits, bringing them very much into focus for markets.

Can China maintain its global hold on the zinc market?

China’s domestic zinc inventories remain stable (if the data can be trusted). The EU and the US look as if they are becoming more dependent on China’s zinc production rather than less dependent. China appears very interested in supply control, maintaining lower prices for its internal market by restricting exports.

China’s strategy appears to be driven by price competition with the US and EU. China appears to want to maintain high prices for export markets making zinc goods from those markets globally uncompetitive.

Cobweb pricing models tend to describe commodity price changes well. Cobweb pricing suggests that China’s behaviour, the recent pandemic supply chain experience, and the Russia-Ukraine war will stimulate investment in zinc.

From a cobweb model one would infer that there would be investment flows from the US and Europe into zinc prospecting and mine development. We might also infer that investment would be directed to regions outside of China and Russia.

However, China holds a key card if its data can be trusted (which could be a significant ask). China’s current stockpiled reserves of zinc are estimated at between 250k and 400k MT.

Global zinc (refined) consumption in 2020 was estimated at 13.2m MT vs. a pre-pandemic run rate of approximately 13.7m MT over the previous five years. Supply in 2022 was expected to reach 14.2m MT (some sources suggest 30% of zinc supply is from recycled or secondary zinc).

Mine production in 2020 printed at 12m MT and Russia accounted for 1.6% or 211k MT of that supply. This suggests Russia accounts for the equivalent or around 40% of zinc oversupply, leaving around 300k MT, which is around or less than China’s zinc stockpiles.

Outlook for zinc prices

We infer, based upon pandemic driven supply chain disruption, sanctions on Russia, renewable energy related demand growth and China’s stockpiling policy, that China can release sufficient zinc supplies back into the market that could cause investors in exploration and production great uncertainty and pain, at least in the short run.

This ability to cause short run pain to investors and or leaving them with a ‘stock overhang’ perception could kill off any ability to unseat China in the longer term. If so, zinc prices outside China will continue their extraordinary rise in response to rising global demand for zinc.

Authors: Christopher Nicholson and Anda Onu – Christopher is ACF’s MD and Head of Research, Anda is part of ACF’s Sales & Strategy team. See their profiles here