Why China wants to control commodity prices

China raised concerns over surging commodity prices and announced measures to curb their rise following the State council meeting on 19 May 2021. Authorities say they want to keep prices lower for consumers, which is a fair goal, but there is much more at stake for the Chinese economy.

To understand why the Chinese authorities are attempting to dampen commodities prices from PGM to softs we observe two underlying factors – the corporate bond market and factory-gate prices. We also examine whether or not the policy will fail.

Key Points:

- Key commodities for the Chinese manufacturing sector are booming in 2021 e.g.:

- Copper prices are up ~31% YTD – US$ 10,159.70/t on 28 May 21 vs. US$ 7,748.85/t on 31 Dec 20.

- Iron ore is up ~32% YTD – US$ 205.74/t on 28 May 21 vs. US$ 155.84/t on 31 Dec 20.

- Increasing commodities costs are passed onto the Chinese manufacturing sector via factory-gate prices (FGP), which is the price of goods leaving factories minus transportation costs. In Apr 21 FGP rose by 6.8% vs. a 4.4% increase in Mar – this is the highest since Oct 2017 where prices rose by 6.9%.

- China’s consumer price index rose 0.9% in Apr vs. 0.4% in Mar, the highest since Sep 20 where CPI was recorded at 1.7%.

- Chinese corporations have bond debt repayments maturing between June 2021 and May 2022 of US$ 1.3trn.

China’s plan

China’s National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) has set out a 5-year plan to attempt to control commodity prices, e.g. iron ore, copper, PGM and corn. The plan will run up to 2025 and involves the monitoring and analysis of commodity prices and trades to address ‘abnormal’ fluctuations in prices – there are no specific targets on the level of price reduction.

The corporate bond market

Chinese corporations have bond (debt) repayments maturing between June 2021 and May 2022 of US$ 1.3trn, 30% higher than in the US and 63% higher than in the whole of Europe (for the same period).

This comes at a time when Chinese borrowers are defaulting on domestic debt at an unprecedented rate. Average monthly domestic defaults in 2H20A stood at CNY 13.6bn (~US$ 2.1bn), up 47% from CNY 9.3bn (~US$ 1.5bn) in 1H20A. In 2020 ~39 companies (domestically and offshore) defaulted on ~US$ 30bn in bonds (Bloomberg).

If China were to tighten monetary policy (i.e. raise real interest rates) in order to control inflation, this would have a negative impact on the bond market – servicing bond coupons will become more expensive as interest rates rise to combat inflation.

Rising interest payments will put more pressure on companies and more of them, inevitably, will default or be forced to make significant costs savings (such as laying off workers or cutting salaries).

Whether companies go bust, cut non-employee costs, or lay off employees some of the effects are the same – more individuals will curtail consumption (spending on goods and services in the Chinese economy) and the personal debt default rate will rise. This amounts to a downward reinforcing negative spiral for the Chinese economy and potentially for Chinese political stability.

Factory-gate prices

In Apr 21 factory-gate prices rose by 6.8% vs. 0.4% in Mar 21. This presents a challenge to exporting goods and to domestic consumption growth.

- If factory-gate prices continue to rise, then the domestic consumption market is affected as consumers will not be able to afford to spend as much on goods and services. Factories will then have to lay people off – resulting in a spiral in the debt problem.

- If export prices increase significantly because the costs of raw materials outweigh China’s competitive advantage on wages (i.e. low labour costs) then China’s competitive advantage would evaporate as its goods become just as expensive as anywhere else in the world, but are arguably of lower quality.

In addition, if indebted Chinese corporations cannot pass on the increase in prices to customers, then they must absorb the extra costs and operate with lower margins. Lower margins mean lower free cash flow and so less ability to service loan interest and make loan capital repayments.

Can China still maintain its competitive advantage?

The NDRC’s decision to try to control commodity prices seems designed to keep China competitive and to avoid raising interest rates to curb inflation pressures and that side effect that will have on corporate borrowers. Rising inflation transfers capital wealth from lender to borrower and over the mid-term, reduces investment and so stifles economic growth.

In a recent note to investors Goldman Sachs (NYSE: $GS) states that China is unable to control commodity price rises.

Controlling commodity prices will be hard for China because increased demand for commodities from Western countries, as a result of economies reopening on the back of fiscal stimuli, will act as a strong commodity price driver.

Furthermore, China may soon lose its competitive advantage (i.e. low labour costs contribution to the total economic cost of production gets smaller and smaller with rising commodity prices). China is already paying a competitive cost because of its ‘indifference’ to environmental concerns.

By losing its competitive advantage on price and because Chinese goods are perceived as low quality, short life span and high volume, China faces a significant economic challenge and potentially rapid decline in its economic growth rate.

The most likely outcome is that China will have to move to compete on quality rather than on price – this change will be driven by political self-preservation and the need for a stable Chinese corporate bond market.

The political deal in China with the populous appears to be ‘less freedom in return for rapid economic growth’. Without the growth part of the equation, the vast new Chinese middle class may begin to question the other half of the deal a little more often and a little more vociferously – this idea may appeal in some quarters, but a less stable China is not an attractive global economic prospect.

In our assessment, controlling commodities prices does not have much of a successful or consistent precedent and in any event, is globally un-enforceable.

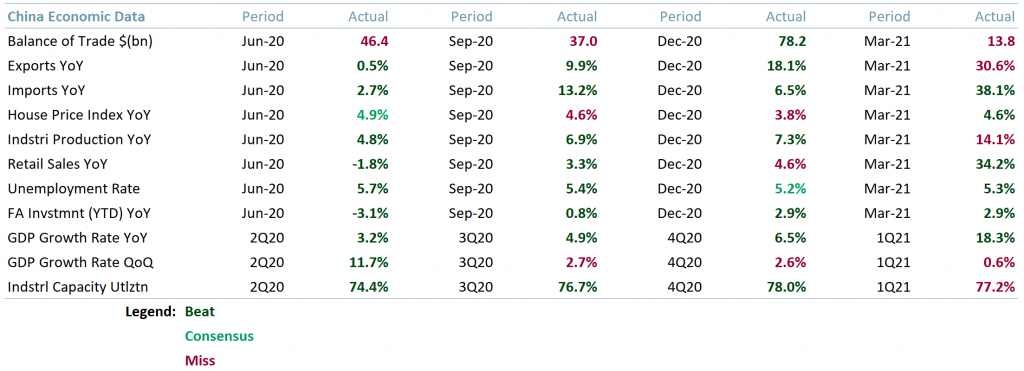

Exhibit 1 – China Economic Data 2Q20-1Q21 (Beat, Consensus, Miss is cf. previous period)

Sources: ACF Equity Research Graphics; National Bureau of Statistics of China

Sources: ACF Equity Research Graphics; National Bureau of Statistics of China

Authors: Sam Butcher and Renas Sidahmed – Sam is a Junior Staff Analyst and Renas is a Staff Analyst and part of the Sales & Strategy team at ACF Equity Research. See their profiles