Saying goodbye to coal – not quite?

Coal usage, as a source of energy, could become a thing of the past (almost) thanks to China’s goal to cut net carbon emissions by 2026 by cutting coal consumption.

Key points:

- Internationally, there is a strong desire and a focus on reducing carbon emissions and fighting global warming by reducing coal consumption. Coal accounts for 39% of annual CO2 emissions from fossil fuels (LNG and coal).

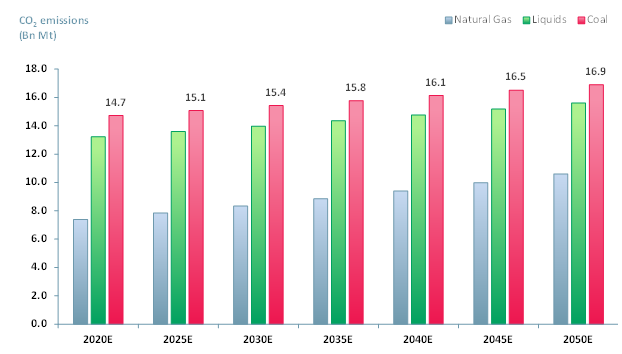

- Even though coal dominates carbon emissions from fossil fuels, we [ACF] forecast that eventually it will begin to level off by 2050E, increasing at a CAGR of only 2.3% between 2020E and 2050E (Exhibit 1). ACF forecasts that Natural Gas and Liquid emissions will grow at a CAGR of 6.2% and 2.8%, respectively.

Exhibit 1 – Global CO2 emissions by fuel 2020E – 2050E

Sources: ACF Equity Research Forecasts; EIA

Sources: ACF Equity Research Forecasts; EIA

- Whereas Europe has made reducing carbon emissions a priority, Asian coal consumption has increased by 25% over the past 10 years. Asia’s consumption accounts for 77% of global consumption whilst China’s consumption alone is 53% of global consumption. (IEA 2019)

- As the world moves towards greener processes, Asia, and in particular China, will require structural changes in order to reduce emissions and bring forward the global net zero CO2 emissions target for 2050.

- New policies and reforms are needed but Asia must tackle deeper problems – the Coal industry is a powerful lobby group.

- Therefore, challenging these regional lobbies to allow for healthy competition with renewables could be a solution. Renewable energy supply

- provides intermittent power as it relies on the weather – the two industries could complement each other during a transition period before battery technology overcomes renewables weak point.

- In addition, freeing the market from long-term supply contracts and price caps will give the much-needed push the renewable sector needs in Asia to replace the coal industry after a transition period.

- Given the energy industry in Asia is mostly state controlled, carbon taxes and market forces designed to change economic behaviour, are not as effective or practical.

Asia must cut CO2 emissions in a timely manner. But the argument that liberally democracies had their time of cheap energy to industrialise and that transition or revolutionary period cannot be denied to other regions and economies has merit.

Industrialisation requires enshrined property rights, vast amounts of cheap energy, and high levels of urbanisation and population density.

Asia is a well-developed continent with a high rate of urbanisation that can now turn to cleaner energy, not by necessity, but by choice. China claims its rate of urbanization was 60.6% in 2019. (National Bureau of statistics of China).

On the other hand, the African continent or Sub-Saharan Africa to be more precise, is vastly underpopulated compared to Asia (43 inhabitants per km2 compared to Asia’s 147/km2 , less than one third. (UN DESA 2019) Sub-Saharan African urbanization rate in 2019 was only 40.7%. (World Bank).

As a result, Africa is only at the beginning of its own industrial revolution, it also does not have either the population density or rate of urbanisation associated with industrial revolutions that have occurred in liberal democracies and in Asia.

So Africa, it can be reasonably argued, deserves a slightly different approach. Sub-Saharan Africa requires an exemption or different set of emissions targets for a period of time before it must retire energy sources such as coal. In a practical sense the transition for Sub-Saharan Africa to entirely renewables should be longer.

In order to give Sub-Saharan Africa room to industrialise fully and to do this sustainably for the planet, Asia and the liberal democracies move faster to cut their own emissions.

Our proposed increase in the speed of emissions cuts requires tougher targets, greater investment and faster delivery of emissions control legislation. It also requires more technological innovation but we are tantalisingly close to having all the solutions required to go fully renewable in a practical way.

Europe, the US and Asia have the structure and resources to cut emissions faster. Sub-Saharan Africa is not yet there.

Sub-Saharan Africa is, however, making headway. In ~50 states, new coal-fired plants are expected to go into production by 2025. Their total annal CO2 output would be 1000 m tonnes, which is the equivalent to ~40% of what Germany’s coal power plants are currently producing (RURAL21 2020).

All countries working together towards a more effective global solution may sound a bit of cliché. However, the C-19 pandemic has created an homogenous urgency to nurture and protect what we have now in order to preserve our futures.

And there is a lot to be hopeful about in spite of the challenges – renewable energy is for the first time looking like an actual cost advantage for companies, investors are certainly thinking this way for all but the most cost efficient carbon energy producers and basic materials producers (oil & gas and mining).